"A steht für Allah"

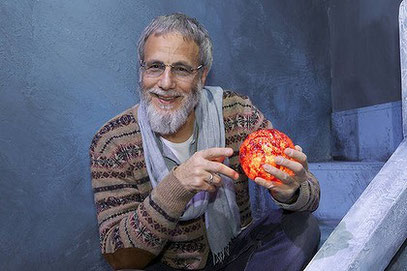

Fast dreißig Jahre wollte er in Ruhe gelassen werden -

obwohl er ein Popstar war:

Cat Stevens, Erfinder von "Morning Has Broken"

und "Peace Train".

Nun heißt er Yusuf Islam und kämpft gegen

die Diskriminierung des Islam.

Im taz-Gespräch bricht er erstmals sein Schweigen:

Eben wurden Sie vor dem Hotel von drei Dutzend Autogrammjägern belagert - fast ein Vierteljahrhundert nach Ihrer letzten

Platte. Stört Sie der ungebrochene Trubel um Ihre Person?

Es ist kein Trubel, sondern eine Erinnerung daran, wie groß mein Einfluss auf das

Leben, die Gedanken und vielleicht auch Träume anderer Leute war. Es stört mich nicht wirklich, aber ich versuche auch klar zu machen: Hier bin ich heute, und ich bin ein Resultat dessen, was ich

gestern war. Es ist eine Reise.

Sind Sie angekommen?

Ja, das bin ich. Und das ist mir heute wichtiger als die Vergangenheit. Ich habe so

viel zu tun, dass ich gar nicht weiß, wie ich das alles bewältigen soll. Die Arbeit für die Kinder, Benefiz-Projekte, die Medien, das Schreiben …

… und die Musik?

1995 habe ich mein eigenes Label gegründet, es heißt Mountain Of Light. In einer Zeit,

da sich die Missverständnisse über den Islam immer mehr häufen, möchte ich mit der Musik wieder als eine Art Lehrer auftreten, um den Menschen islamische Musik und Kunst näher zu bringen. Wenn

Sie sich meine jüngsten Lieder anhören, werden Sie überrascht sein über die Entwicklung des Stils, des Genres.

Die Menschen mochten Ihren alten Stil ja ganz gerne.

Unlängst habe ich in London ein Benefizkonzert gegeben zugunsten der muslimischen

Schule in London, die wir vor genau zwanzig Jahren gegründet haben. Es war ausverkauft.

Es war Ihr erster Auftritt seit sehr, sehr langer Zeit …

… mein erster Auftritt auf einer englischen Bühne seit 27 Jahren. Und es war großartig,

ein ganz besonderer Abend.

Haben Sie auch alte Stücke gespielt?

Ich habe drei neue Songs gespielt. Einer heißt "I Look, I See", ein anderer "God Is The

Light" und der dritte "Wind, East And West". Und dann spielte ich noch "Peace Train". Der Song ist sehr nah dran an den Realitäten heute, gerade vor dem Irakkrieg, als es viele

Antikriegsdemonstrationen gab. "Peace Train" ist wie eine alte Lokomotive, er ist für die Ewigkeit gebaut.

Aber lange wussten Sie nicht, wohin die Reise geht.

Stimmt, die Fahrkarte war kostenlos - aber ich wusste lange nicht, wohin mich der Zug

bringen würde.

Fühlen Sie sich berufen, zwischen dem Islam und der westlichen Welt zu vermitteln?

Ich will nicht Sprecher derjenigen sein, die den Islam nicht repräsentieren - das zu

sagen, ist mir wichtig. Aber ich möchte versuchen, den zivilisierenden Beitrag zu unterstreichen, den der Islam in dieser Welt leisten kann und auch schon geleistet hat.

Für Zivilisation im Sinne eines aufgeklärten Bürgertums steht der Islam ja nicht unbedingt und überall.

Stimmt, mit der Zersplitterung der islamischen Welt sind die Probleme nicht kleiner

geworden, eher größer. Aber können wir dem Islam dafür die Schuld geben? Das liegt doch auf der Hand: Es gibt so viele islamische Länder, die alle auf ihre Art versuchen, sich in dieser

globalisierten Welt zu behaupten.

Motor der Globalisierung sind die USA. Hegen Sie Groll gegen sie?

Ich glaube, die USA sind ein naives Volk, nicht annähernd so weit entwickelt wie die

europäischen Nationen. Deswegen machen sie so viele Fehler. Wie weit kann Amerika gehen? Soll die Welt amerikanisch werden? Ich glaube nicht. Sie müssen mit anderen Kulturen in Frieden

zusammenleben, nur so können sie selbst prosperieren. Ich meine, schauen Sie sich George W. Bush an. Er sollte diesen Job nicht haben, er dürfte diesen Job nicht haben - und jeder weiß

das!

Wäre, wie Sie sagten, Bob Dylan der bessere Präsident Amerikas?

Nein, die Zeiten haben sich verändert. Wie er selbst gesungen hat, "the times they are

a-changing". Gegen die Hegemonie der USA muss trotzdem ein Kraut gewachsen sein.

Mit Atomwaffen - wie Iran? Mit Bomben - wie al-Qaida?

Mit vielen Menschen ist schlecht umgegangen worden. Und manche Menschen reagieren wegen

ihrer Frustration und Ignoranz komplett unislamisch. Deshalb ist es wichtig, hier die Wahrnehmung zu verändern. Der Islam ist nicht nur eine Botschaft für die arabische Welt. Der Islam ist eine

spirituelle Botschaft. Das wird gerne vergessen.

Und daran wollen Sie erinnern?

Das drücke ich in meinen neuen Songs aus. Ein Titel wie "God Is The Light" - was könnte

profunder sein? Wenn man das erst einmal verstanden hat …

Wann haben Sie denn verstanden?

Ich war glücklich genug, die Chance gehabt zu haben, den Islam ganz privat und ohne den

Einfluss irgendeines Muslims studieren zu können, der mir sagt, wie ich das zu verstehen habe. Ich las einfach nur den Koran, ganz alleine.

Was hat Sie denn damals, 1977, daran interessiert?

Seine Authentizität. In der Bibel ist alles von den Evangelisten interpretiert, mal so,

mal ein bisschen anders. Der Koran ist erhalten, wie er damals aufgezeichnet worden ist. Ich war ein Freidenker, ich hatte keinerlei Barrieren. Ich glaubte nicht an Barrieren. Also wusste ich

nicht, warum ich nicht den Koran lesen sollte - obschon er mit einigen Tabus belegt war, die in meiner Kultur begründet waren.

Welche Kultur war das?

Aufgewachsen bin ich als Christ, ich bewunderte gewisse Aspekte des Buddhismus - und

fand all das vortrefflich auf den Punkt gebracht im Koran.

Warum haben Sie seinerzeit die Fatwa gegen Salman Rushdie unterstützt?

Habe ich nicht, das war die Falle eines Journalisten, das war Politik. Ich wurde in

einem völlig anderen Rahmen danach gefragt, was mit Leuten geschehen solle, die den Namen Gottes verhöhnen. Und als gelehriger Schüler des Koran habe ich rezitiert, was für solche Fälle

vorgesehen ist. Es ist Politik. Und was Politik bedeutet, das zeigt uns schon das Schicksal von Julius Caesar: Dolchstöße in den Rücken. Mit dem Koran, mit der Botschaft des Islam, die mich so

beeindruckt hat wie nichts anderes, hat das gar nichts zu tun.

Was hat Sie denn nun so sehr beeindruckt?

Die Idee des Einen Gottes. Wenn Sie das verstehen, verstehen Sie das

Universum. Und Sie verstehen, warum Leute sich bekämpfen - weil sie sich weigern, die Herrschaft des Einen anzuerkennen, der die Regeln des Lebens vorgibt. Ich sah es als einen Weg zum

Frieden und zur Linderung.

Für Sie selbst - oder für die ganze Welt?

Speziell für mein Leben. Der Koran half mir, auf die Füße zu kommen und mein eigenes

Leben zu leben.

Als ob Sie das vorher nicht getan hätten! Sie waren ein Weltstar!

Ich war ein Popstar und lebte das Leben eines Popstars. Aber ich war gefangen in meiner

kleinen Kapsel. Nicht dass ich da nicht hin und wieder ausgebrochen wäre. Ich hatte viele Freunde, die nicht unbedingt Showbiztypen waren - aber ich saß dennoch in dieser Kapsel, die es mir

unmöglich machte, mit meinem gewöhnlichen, echten, wie soll ich sagen … mit meinem unprätentiösen Selbst in Kontakt zu treten. Das hatte ich für eine Weile verloren.

Viele Ihrer Songs handeln von einer spirituellen Suche …

Ja, ich habe mal geschrieben (denkt lange nach) … es ist aus "Sitting" … "I'm not making love for anyone's whishes / Only for that light I see / 'Cause when I'm dead and lowered

low in my grave / That's gonna be the only thing that's left of me". Das ist das Licht der Liebenswürdigkeit, nach dem ich mein Leben auszurichten versuchte. Manchmal habe ich es verfehlt,

manchmal verblasste es. Aber es drückte die Liebe aus, die ich dem Leben selbst gegenüber empfand.

In "Where Do The Children Play" singen Sie die prophetische Textzeile "They keep on building higher till there's no more

room up there".

Ja, "Wolkenkratzer füllen den Himmel, und sie bauen immer höher, bis dort oben kein

Platz mehr ist".

Nach dem 11. September bekam das einen etwas seltsamen Beigeschmack.

Es war völlig verrückt, völlig verrückt. Andere Sachen auch. Das gibt's den Song

"Tuesday's Dead" mit der Textzeile "Where do you go when you want no one to know", wissen Sie, das ist schon sehr, sehr merkwürdig (lacht). Aber das Interessanteste war, was ich in "On The Road To Find Out" geschrieben habe: "Pick up a good book", nimm ein gutes Buch in die Hand. Ich bin sehr

froh, dass ich nicht "the book" geschrieben, dass ich mich da nicht festgelegt habe. Es ist völlig egal, welches Buch dich dorthin führt.

Also gibt es immer noch "a million ways to be", auch für den strengen Muslim?

Ach, das ist doch das Dilemma: Wenn wir die Wahl haben, haben wir auch die

Verantwortung. Das ist es, was viele Leute vergessen, diese mitfühlende Liebe zum Leben als solche. Die Leute gehen im Laufe der Jahre immer konformer damit, was die Welt von ihnen will. Sie

verlieren ihre Kindlichkeit, wenn Sie so wollen.

Sie selbst haben fünf Kinder. Welchen Rat würden Sie ihrem achtzehnjährigen Sohn geben, wenn er Rockstar werden

wollte?

Ich würde ihm zu Flexibilität raten. Manchmal müssen Menschen eine Wahl treffen,

manchmal machen sie Fehler, und dann müssen sie aus diesen Fehlern lernen. Solange Sie ein leitendes Prinzip haben, können Sie es durch die Prüfungen und Probleme des Lebens schaffen. Mein Sohn

hat bereits einige Songs geschrieben, das wird noch interessant.

Was hat es mit der muslimischen Schule auf sich, die Sie in London gegründet haben?

Es gab zu diesem Thema schon vorher viel Blabla, aber keine Lösungen. Es gibt Schulen

mit christlichem Religionsunterricht - und nun gibt es auch eine Schule mit Islamunterricht. Das ist auch schon alles, es ist keine Koranschule.

Der Islam kann doch in jeder säkularen Schule gelehrt werden.

Im Laufe des Lebens gibt es eine kontinuierliche Säkularisation … hm, wie ist das mit

der Religion in der Schule in Deutschland?

Man kann es sich in der Regel aussuchen.

Wenn das so ist, bleiben dem Islam einfach nur ein paar Seiten im Sozialkundebuch. Das

ist zu wenig, denn der Islam hat mehr zu bieten. Wenn Sie sich anschauen, dass die Propheten ausgesandt wurden, um die Welt zu verändern - das hat mehr Aufmerksamkeit verdient als ein paar Seiten

im Sozialkundebuch.

Was meinen Sie mit Aufmerksamkeit? Mehr beten?

Das erste Lied, das ich nach meinem Übertritt zum Islam geschrieben habe, war für meine

kleine Tochter, die gerade das Alphabet beigebracht bekam. Das Lied hieß "A Is For Allah". Ich wollte meiner Tochter beibringen: Vergiss die Äpfel, sie sind nicht das Erste, woran man denken

sollte. Das Erste, woran man denken sollte, ist der Schöpfer der Äpfel, der Schöpfer von allem. Wenn Sie das wissen, wissen Sie, was wirklich wichtig ist.

Trotzdem: Wie konnten Sie den Drang nach künstlerischem Ausdruck von heute auf morgen verlieren? Islam und Musik schließen

einander doch nicht aus.

Den Effekt, den die Lektüre des Koran auf mich hatte, kann ich am besten mit einer

Metapher erläutern: Ich stand da mit einer Kerze in meiner Hand - und plötzlich war die Sonne aufgegangen. Was soll ich am hellen Tag mit einer Kerze?

Und danach haben Sie tatsächlich alle Ihre Instrumente verkauft? Haben Sie sich wirklich von einem Tag auf den anderen so

sehr verändert?

Sie verändern sich nicht wirklich, wenn Sie ein Muslim werden. Aber was passieren

sollte, ist, dass Sie die wahre Essenz dessen erkennen, was Sie wirklich sind und in diesem Universum erreichen wollen.

Musik lenkt davon ab?

Eigentlich schon, ja. Zumindest mich (lacht).

Es heißt, Religionen wie der Islam könnten nur in der Wüste entstehen

In der Einöde, genau! Jesus ging in die Wildnis, Mohammed auf einen Berg namens "Berg

des Lichts". Fernab von den Versuchungen der Zivilisation.

So wie Sie?

So wie ich.

Millionen Fans haben das nicht verstanden. Und die Leute, die vorhin vor dem Hotel auf Sie warteten, wohl auch

nicht.

Okay, dann will ich es so erklären: Sie sind in einem dunklen Raum und können die Dinge

ertasten. Dann kommen Sie an den Lichtschalter und können plötzlich die Dinge sehen, wie sie wirklich sind. Das ändert nichts an den Dingen, aber an Ihrer Einstellung dazu. Sie fangen an, die

Dinge zu akzeptieren. Ja, Akzeptanz ist das richtige Wort. Gestern habe ich mit dem Hollywoodschauspieler Christopher Reeves geplaudert, der im Rollstuhl sitzt, und er sagte: "Die wichtigste

Lehre für mich war es, mein Schicksal zu akzeptieren."

Und das heißt?

Das meiste Unheil auf dieser Welt rührt daher, dass die Menschen unbedingt, unbedingt

versuchen, es zu kontrollieren. Aber das geht nicht, das geht nicht. Was uns fehlt, ist Demut.

Christopher Reeves hat für diese Erkenntnis einen hohen Preis bezahlt.

Aber wer weiß, wohin es führt? Es gibt so etwas wie eine universelle Gerechtigkeit. Und

alles, was uns zustößt, führt am Ende zu etwas Besserem. Davon bin ich überzeugt.

Große Musiker wie Leonard Cohen oder Van Morrison hatten immer auch eine spirituelle Seite - und dennoch verzichteten sie

nicht auf die Musik.

Einige dieser Leute, von denen Sie sprechen, habe ich unlängst getroffen. Ich bin

verblüfft darüber, wie groß mein Platz im Herzen auch befreundeter Künstler ist …

Was ich tat, tat ich ganz naiv, einfach weil ich dachte, ich müsste es tun, ganz

natürlich. Heute geben mir viele der ehemaligen Pop- und Rockkollegen Recht. Ich habe mal eine Textzeile geschrieben, "I'm not the only one", die dann auf einmal von John Lennon adaptiert wurde.

In "Imagine". Ich konnte es nicht fassen: John Lennon sang eine Zeile von mir!

Sie haben früher Ihre Albumcover selbst gestaltet. Malen Sie eigentlich noch?

Oh nein, ich benutze Adobe Photoshop! Ich liebe Computer!

Der Islam bevorzugt ornamentale Kunst.

Was daran liegt, dass die Menschen beginnen, die Dinge unter Gott zu verehren - nicht

Gott selbst. Es ist ein Ratschlag, das Eigentliche nicht zu vergessen. Das gilt für viele Bilder, vor allem im Fernsehen. Mit dem wahren Leben hat das Fernsehen nichts zu tun, und doch ist es für

viele Menschen ein Ersatz für und eine Flucht vor dem richtigen Leben. Ich versuche, etwas zu schaffen, dass einen lehrreichen Effekt hat.

Nicht alle Menschen wollen belehrt werden.

Das Wort "Ignoranz" bedeutet: Ich weiß, dass etwas da ist - aber ich ignoriere es. Ich

gehe nicht los, es zu suchen. Also bin ich ignorant.

Verstehen Sie sich als Prediger?

Prediger? Nicht wirklich. Ich mag das Wort "Prediger" nicht, da bekomme ich eine

unangenehme Gänsehaut. Lehrer sind dann am besten, wenn sie den Hunger auf Wissen schüren. Wenn sie nur predigen, dringen sie nicht zu den Schülern durch. Ein inspirierender Lehrer bringt die

Schüler dazu, empfänglich zu sein für das, was er lehren will.

Musik ist im Islam ebenfalls sehr wichtig.

Im Koran steht, dass die guten Dinge, die Gott uns gegeben hat, durchaus genossen

werden dürfen. Nur wenn es korrumpiert wird und fault, dann ist es verboten. Erlaubt sind beispielsweise Hochzeitslieder, positive Lieder. "Morning Has Broken" ist ein perfektes Beispiel dafür,

auch "Peace Train".

Ihre Songs waren islamisch, lange bevor Sie es wurden?

Ja (lacht), sie sind mir vorausgegangen.

Musik kann Vehikel zur Erleuchtung sein. Im Techno beispielsweise tanzen sich die Menschen in Trance - was soll daran faul

sein?

Ich gehe nicht in Diskotheken, eben deswegen. Nicht weil ich da Vorurteile hätte.

Sondern weil es mich nirgendwo hinbringt. Was dort gespielt wird, dient nur dem Geldverdienen. Es ist ein Geschäft. Deswegen heißt es ja auch Musikgeschäft.

Es ist aber auch ein Genuss.

Leute wollen die Sinne, die Gott ihnen gegeben hat, möglichst effektiv nutzen. Sie

halten das dann schon für das Leben als solches. Wenn sie nicht sehr gut aufpassen, können sie diese Sinne sehr schnell verlieren. Wer zu viel Musik hört, verliert sein Gehör. Viele

gesundheitliche Probleme rühren daher, dass die Menschen ihre Sinne allzu stark reizen. Ich halte mich fern davon, das ist nicht mehr mein Leben.

Sie hören keine zeitgenössische Musik?

Nein, nicht wirklich. Nicht viel.

Nicht viel? Was denn?

Travis, Coldplay. Und die Flaming Lips, ganz großartig. Eine unglaublich interessante

Gruppe.

Die haben auch ein sehr spirituelles Element in ihrer Musik.

Und Elemente von Cat Stevens! Kürzlich erst mussten sie zugeben, dass sie für "Fight

Test" auf dem Album … na, wie hieß das doch gleich …

"Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robot"?

Ja, sie haben die Melodie von "Father & Son" geklaut. Mir wäre es egal gewesen,

aber die Plattenfirma reagierte gereizt. Ich fand's fantastisch. Es war ein Kompliment. Ich liebe das Lied. Wenn sie den Bereich des geistigen Eigentums betreten, wird's sehr schwierig, weil

jeder bei jedem borgt … (sieht aus dem Auto heraus einen Dönerladen namens "Ali Baba") Oh, "Ali Baba"! Ali Baba …

mein Vater sagte immer, wenn er einen Araber sah: Ali Baba.

Herr Islam, als Cat Stevens hatten Sie stets abgekaute Fingernägel …

Ja, ja, schlimm. Jetzt sind sie frisch manikürt, oder?

Sind sie. Verbietet der Islam das Fingernägelkauen?

Natürlich nicht! Ebenso wenig wie das Rauchen, das ich ebenfalls aufgegeben habe. Als

ich den Einfluss gesehen habe, den das Rauchen auf Menschen haben kann, habe ich es aufgegeben. Ich saß einmal im Kino neben einem Raucher, und als ich dieses ekelhafte, angeekelte Gesicht

gesehen habe, gab ich es instinktiv auf.

Sie essen koscher?

Ich versuche, mich daran zu halten.

Ihre Frau ist verschleiert?

Ja, aber es war ihre Entscheidung. Muss ich den Sinn des Schleiers erklären? Es geht

nicht um Schleier oder Schwein. Es geht darum, Lebensführung aus einer Quelle zu beziehen, die nicht angezweifelt werden kann. Viele Dinge tun wir aus dem Glauben heraus. Aber im Islam fand ich

ein hohes Maß an Logik.

Welche Logik?

Bei allem, was irgendwie funktioniert, gibt es einen Verantwortlichen. Also muss es

einen Schöpfer geben, es muss einen Kapitän dieses Schiffes geben!

Die Idee des "unbewegten Bewegers" gibt es aber auch schon seit Aristoteles.

Genau! Blättern Sie nach, wo Sie wollen! In der griechischen Philosophie, in der Bibel,

in den Veden, in den Upanishaden. Was ist das erste Gebot? "Du sollst keinen anderen Gott neben mir haben"! Das ist keine politische, keine kulturelle, sondern eine universelle Erkenntnis.

Es gibt aber in einer desintegrierenden Welt so viele verschiedene Angebote, die metaphysisch Obdach

gewähren.

Richtig, und das verwirrt mich schrecklich. Das war es, was mich am Islam so berührt

hat: Du kannst nichts finden, das wahrer wäre.

Und Sie haben die Suche endgültig aufgegeben?

Nein! Würden Sie mir jetzt, in dieser kostbaren Sekunde, etwas zeigen, dass wahrer wäre

- ich würde es akzepieren. Aber das gibt es nicht...

[taz.de, 01. Nov. 2003]

What was the first record that you ever bought?

“Baby Face” by Little Richard. I was fascinated by the way he did these curly things with his voice.

Is it true that you were deeply affected by the film West Side Story [1961] when you saw it as a teenager?

That’s true. I was interested in the lifestyle it showed because it was the archetypal life on the street, which has to do with one

gang dominating another. I was spending most of my time on the street then, so that’s probably why it interested me.

You were at the peak of your career during a period when rock stars were elevated to an extraordinarily exalted position in the culture. The music industry that fostered that phenomenon

has dissolved and been replaced by the Internet, which has changed the relationship between musicians and their audience. Has the public perception of musicians changed?

It’s true that the Internet is an equalizer, and everybody can be a star now. Musicians are more touchable these days, and that’s a

good thing. It’s certainly the way I like to live my life, and it’s why I don’t do concerts in big arenas—I prefer to be in touch with my audience.

When you were at the height of your success, did you enjoy it?

Yeah. Nobody could not enjoy being the center of attention and having such adoration. But I felt that it was a responsibility, too,

and I often changed my track so people couldn’t predict where I was going next. I didn’t quite know myself, but I was trying to be sincere whichever direction I went.

What's the most dangerous thing about fame?

Vanity.

Can you recall the first time you experienced a sense of divine presence?

It was when I was a kid, praying at school—prayer was always with me. I attended a Catholic school, but I was officially Greek

Orthodox, so I couldn’t take part in many Catholic rituals. That led me to be a kind of observer within the Christian faith, and allowed me to maintain my belief in God without being tied to any

particular denomination.

During the mid-'70s, you devoted most of your time to searching for some kind of spiritual anchor. What prompted that?

Being larger than life, or being projected as such in the music business, leads you to question yourself. Some people try to forget

about it by taking drugs or too much drink, but I was never like that. I was aware that there were very serious, big questions, and I was petrified about what might be in store for me.

What did you find in the Islamic faith that was lacking for you in other spiritual paths?

It was the most direct and encompassing message I’d ever encountered. I was confused by many of the spiritual books because they

used metaphysical and theological terminology I didn’t understand. But the Koran was very clear, especially about the fact that every soul eventually must meet its Maker and then be questioned.

That, to me, was a wake-up call.

What's the most widely held misconception about Islam?

That there’s no link between Islam and Christianity and Judaism. There wouldn’t be Islam if there wasn’t Christianity or Judaism,

because it’s all one long line of revelation. Seeing it from that point of view it makes you ask yourself why Muslims sometimes separate themselves from that large family that leads to Abraham

and, even before that, to Adam. The only answer is that we’re conditioned to do it by thinking, Hey, I do things better than he does.

Did you miss music during those 28 years you were away from it?

No, because I made my life my art. I’d been singing and composing songs for years, and you can lose touch with life if you don’t

start living it. That was very important for me because I’m a realist as well as a surrealist. I love to touch life, and that’s what had to happen. I got married and had kids, and there’s nothing

more astounding than having your kids look you in the eye, wanting to know what it’s all about.

Much of your music of the early '70s explored romantic love as understood in conventional Western terms. In 1979, you entered into an arranged marriage, which suggests that your views

might have changed. Did they?

Love has many levels, and love of God is very profound. It’s certainly more lasting.

Why are spirituality and sexuality so often at odds with each other? It seems that most spiritual belief systems have a difficult time integrating those two energies.

The sexual act—separating that from love itself—is centered solely in the body, whereas spirituality is connected to the whole self.

Whether it’s a female, a taste, or a sound, all these beautiful things affect our self. We are the perceivers of beauty, and that’s why sex doesn’t quite go far enough. You can go much further

with the spiritual.

Have you done the hajj [an arduous pilgrimage to Mecca, which all Muslims are obliged to perform at some point in their lives]?

Yes. It wasn’t difficult because once you’ve decided to do something, you’re able to overcome any obstacles that appear. You can

deal with it because you know what you’re doing it for.

What's your definition of sin?

God has decided the rules of life, whereby you don’t trespass on anybody else’s rights, and sin is something that upsets the balance

of things. There are three types of sin: sin against yourself; sin against other people; and sin against God. People often sin against themselves and others and misbehave with God, too.

What's the difference between knowledge and wisdom?

Knowledge is a thing you can carry around with you, but you may not apply it. Some knowledge is indiscriminate, and it can be

damaging. I recently found a wonderful definition of wisdom: It is that thing which results in the maximum good and the least harm.

What's the greatest privilege of youth?

Naïveté. That’s a great thing because it makes a fresh outlook possible. We need kids to remind us of how incredible this world is.

People are increasingly losing their childhoods too soon, and that’s a danger. There’s a prophesy somewhere that at a certain point in history, children will be gray. It’s weird to think about,

but it’s possible.

When did you become an adult?

I don’t think any of us really do that, if we own up to it. I’m still about 17.

What aspect of the future, as you envision it, is the most disturbing to you?

There’s a common threat facing all of us—Christians, Jews, and Muslims—and that is the Antichrist. It’s a very deep subject, and

it’s a horrendous thing to contemplate. Someone will appear who is, in fact, the opposite of what he appears to be. Some people will believe in him, and that’s really frightening. In Islam,

there’s a belief that Jesus will return to destroy the Antichrist, which is something many people don’t know about the Islamic faith.

When you returned to music in 2006, did you have any doubts that it was the right thing to do?

No, because it was leading me toward a bridge, and bridges are good. We need them to cross over some of these torrential

waters.

You're currently working on a musical, titled Moonshadow, that's slated to open in London later this year. What's the story there?

I’ve been working on it for six years, and it’s not finished yet, but it will actually see the light of day this year. It’s a story

about a world of darkness where only the moon shines, so people have to survive in a sunless world. The central character is a young boy who has a vision of another world where the sun shines

every day and people are at peace. He shares his dream with his school friend and promises that he’ll take her to this world one day. Things go wrong for him as he grows, then he meets his

moonshadow, who gives him the courage to seek that world of the lost sun. It’s an epic, everyman story, and it’s autobiographical, too. I met Paulo Coelho yesterday, and I told him how much the

play was inspired by The Alchemist.

What are you currently listening to?

I’ve been listening to George Harrison. Klaus Voorman recently made a record for his 70th birthday and asked various musicians to

select a song he’d played on and do a duet with him. Klaus played on most of George’s records, so I chose “All Things Must Pass” and “The Day the World Gets Round.” I love listening to George’s

music again—his spirit is fantastic.

Your son is a musician. How did you feel about him going into the music business?

I had some trepidation about that, but he has his own views about what he wants to do, and I have to accommodate that. My son

advises me a lot these days. He introduced me to the Red Hot Chili Peppers because he wanted me to hear the production on their records. It was quite impressive, I must say. He also likes Eddie

Vedder, who I met recently. I happened to be having breakfast at Shutters [the Los Angeles hotel] one day, and Sean Penn was across the room. We kind of clocked each other, then made arrangements

to meet the next day, and Sean brought Eddie along to breakfast. He’s got a great aura about him.

Are there Musicians who you would like to work with?

I’d like to work with Bob Dylan someday. His son Jesse did a lovely film for a new song that didn’t find a home on this album.

It’s kind of a joke song about the incident in 2004 when I was on my way to the States to make a record and was denied entry into the country.

[Ed. note: Available only as a single, Yusuf’s song about the incident, “Boots & Sand,” features Paul McCartney and Dolly Parton.]

How do you feel about America?

America was my home for a very long time, and it’s a fascinating, pioneering country that many people look to. In the recent past it

hasn’t been doing very well, but there’s a great new hope now with the election of Obama. America took a very big leap there and proved that it still has the edge as far as being able to do

things many other countries may find difficult.

[May 2007 - Interview by Kristine McKenna/ Los Angeles–based curator and writer]

The artist formerly known as Cat Stevens is starting a new chapter - one that has been in the making since the day he first picked up a microphone.

Rock icon Yusuf Islam - who goes by the single name Yusuf these days - is putting the finishing touches on what he calls a lifelong dream, Moonshadow: A Musical Fantasy. Set to premiere

in Australia on May 31, the production is a mix of the artist's hits from the 1970s with a string of fresh songs penned for the play.

The musical represents a summit of sorts - topping a storied and at times controversial career that has seen Yusuf go from triple-platinum award winning musician to a man on

the verge of abandoning his craft forever.

Yusuf spoke to Al Jazeera about that journey during a stop in Doha, Qatar following his first concert in the Middle East.

You’ve talked before about your journey through music, saying that you put down the guitar after converting to Islam and then picked it back up again. What is your view on the

intersection of faith and music?

At one point, perhaps music was my religion. For a lot of us growing up in the West in the early '60s and then '70s, music was

a way of life. It was a way to express ourselves. I was a serious dreamer and I was looking for the truth. It was only when I finally bumped into Islam through a gift of the Quran that

I realised that all the answers I needed were there.

I was still making records, but I lost my interest. I found something that was so much more pure and sacred, so I asked

the imam at the mosque in London about music and he said 'there’s no problem’. But I had some doubts, because there were other brothers who quoted opinions that 'there’s a consensus that

music is haram (forbidden)'. When you’re a new Muslim, you’re very careful of what you do. So I tread very carefully. I decided because of the almost insulting approach

that the media took to me upon embracing Islam that I had had enough of that, so I didn't bother to continue.

After [the 2001 attacks of] September 11, there was

a serious crisis. We were facing Armageddon almost and it seemed that now we needed to build bridges back to our middle ground, because the extremes had been exposed. Therefore I sang

Peace Train again. It was just a cappella, but that was the beginning.

It was my son who finally brought guitar back into the house. When I picked that up, I suddenly realised: I've got another

job to do.

What was it that your son said that made you want to pick up the guitar again?

He didn't say anything. He just left it, and I was surprised that I remembered where my fingers should go.

What would you tell other Muslims who have a passion for music but are also trying to walk this line - this schizophrenia of sorts that oscillates between 'music is

good' and 'music is forbidden'?

As far as sacred texts are concerned, they cannot be ambiguous. There are no gray areas. When it comes to music, there is

no word 'music' in the Quran. Obviously there are insinuations and implications and situations where music is being played and its haram because there’s drinking and fornication

- well that’s sex, drugs and rock and roll. But in the end, it is the interpretation. So yes, I believe there is haram music and yes, I believe there is

halal (permitted) music.

Is there an over-arching theme in your music or an outward meaning of your songs you want to convey?

I tell stories. I try to tell true stories. It's about how people live and what their problems are - how we love and fall into

trouble and bleed and laugh. That’s ended up being the theme of the musical that I'm writing and that I’m going to put on in Australia at the

end of May. It's all to do with journey. There are only two types of stories: those about leaving home and those about coming back.

Where did the idea for your musical Moonshadow come from?

I grew up on the West End of London surrounded by theaters and musicals and I always dreamt of writing a musical. It happens that

now I have the perfect opportunity, after having written so many songs. It's a story about a world where there’s no sun and no day, only night. There's only one moon providing

natural light. That means everybody has to work extra hard to buy these embers to keep their houses warm. In the middle of all this, there's a boy who has a dream about another world - the World

of the Lost Sun, called Shamsiya. He meets his moon shadow and he decides to go on a journey to find that World of the Lost Sun.

What is your creative process like and where do you get the inspiration for your songs?

That’s a difficult question. I’m unscientific about it all. There’s a mood and I catch the mood. I entertain myself. I’m

the first one to hear the song, and if I like it, perhaps others will like it too. There was a great philosopher who once said 'there's nothing more joyous than the joy of that child who

creates something and then shows it to others'. It’s being gifted.

What happens when you give that gift and it is not received in the way you want it to be? Particularly after your conversion, and after you starting making more

Islamic-themed songs, was there a backlash?

You go through various phases. Living up to your ideas is not an easy job and when other people have ideas of you that you have to

live up to as well, it's even harder. That’s why we have a clear direction from our Lord as to how to live. As long as you keep your focus on God and his prophet I dont think you can be

diverted. It's all down to that intimate and direct relationship and that's what you maintain in your prayers. So yes, it was difficult. But I always had my prayers.

Let's talk about your song "My People". You’ve said before that you were looking at the events of Cairo's Tahrir Square [during the Egyptian

uprising]. What was the greater inspiration and what did you hope the song would do?

There wasn't much we could do sitting and just watching [the uprising] on television. We wanted to contribute and that was the best way I knew how - to write a song. We got people from around the world to contribute their voices to the

cause and we put out a call on Facebook. I sang a demonstration of what the key should be and they sang the chorus and sent it back. We got all the voices

on the track and then made it for free.

To what extent does music have the ability to change people's perceptions and the lens through which they see?

I don't focus on that and I think that’s important, because if a person thought he had control over others' lives that would be

frightening. Everybody has a part to play and if I've got a song to sing, I sing it. If it affects people, now I just say alhamdulilah (praise is due to God).

But it does go two ways. When you do finally break through the wall of the business and reach people - which is what

everyone wants - they have an effect on your direction.

What advice do you have for young people starting out and looking at art as a way to contribute to civilisation?

It is a high wall to climb. It was probably shorter in my day. It's not an easy world right now for any profession. But if you can,

then try. As I once wrote - 'if you want to sing out, sing out; if you want to be free, be free; if you want to be me, be me'. Well (laughing) - you can’t really do that last one.

[Al Jazeera/ 18.04.2012]

(ein Artikel hierzu)

No about-face in converting to Islam, says Cat Stevens.

THE long spiritual journey of Yusuf - the artist formerly known as Yusuf Islam, and before that as Cat Stevens, and somewhere in the mists of time as plain old Steven Georgiou - began when he

fell ill at the height of his first blaze of fame in the late 1960s.

''My first experience was a dazzling one, as an 18-year-old with a hit record and girls chasing me all over Europe,'' he says during a relaxed 45-minute chat

in the upper circle of the Princess Theatre, where his musical Moonshadow this week had its world premiere. ''There I was on tour with Hendrix and

everything that was a consequence of that. I didn't learn that much, I just succumbed to the moment, and that was stardom.''

Did you, like Hendrix, succumb to drugs too? ''For sure, we all did that. And because of that I contracted tuberculosis [at 21]. That was an important inoculation,

because I knew then that whatever I did next I must keep more control, I must keep my own interests at heart, and not worry too much about what the manager and agents, and even the public, were

saying.''

By the time Stevens retired from the world of pop music in 1979, it seemed he had given up listening to the fans altogether. Two years earlier he had formally embraced Islam, and on July 4, 1978

he officially changed his name to Yusuf Islam. ''It really was independence day for me - me choosing my name and my own destiny,'' he says. (For the record,

he also chose the name Cat, which many people still use when they address him.)

Although he made music for kids in the years that followed, it wasn't until 2001 that he began to edge back towards the songs that made him famous. With Moonshadow, he has finally come

full circle, weaving dozens of his most famous tracks, and a few new ones, into its mystical, mythical story.

He left behind the songs and persona of Cat Stevens, Yusuf says in a slow voice that rarely rises above a whisper, ''because I found something I was so much more

excited about. I didn't need to search any more in the musical world because I'd done it, I'd climbed the mountain, I was looking down and saying, 'Well, where next?'''

It's been a long process, this coming back to his music. It was driven, he says, by a desire ''to start bridging some of my dreams unfulfilled'' -

specifically, the desire to write a musical (famously, he spent his early years above his parents' restaurant on Shaftesbury Avenue, in the heart of London's West End).

But for a long time it felt wrong to do it. There is some debate, he explains, within Islam over the value of musicians, of entertainers, and that's why he dropped the ''Islam'' from his name,

publicly at least, in 2006.

Coughing up blood and watching many of his contemporaries fall by the wayside gave the young Stevens the impetus to start probing ''the real serious questions of

life and death'', but Islam was not his first stop. Along the way he dabbled with meditation, Hinduism, I-ching. At the outset, he concedes, he was just following the fashion of the day -

''The Beatles had something to do with it; it was a trend'' - but by the time he got to the Koran, he says, ''I think I was

ready for something as big as that''.

Not everyone was ready for his change of direction, though. He talks of ''the fans I left behind'' but says the appearance that he had done an about-face was

mere illusion. ''From one stage to another may appear vastly different but it's one direction,'' he says. ''Upward. I

hope.''

The greatest strain came in 1989, with reports that he had supported the fatwa issued on writer Salman Rushdie over his novel The Satanic Verses. For the first time, Yusuf bristles

slightly.

Do you feel you were misrepresented?

''Of course. That's why one of the first songs I sang on my return album was Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood. I believe in peace and I think anybody that

disturbs the peace, it's their fault.''

At first blush, it sounds like he's blaming Rushdie for all that happened, but as he continues it's clear he is at the very least also blaming himself for being sucked into the media storm.

''I was gullible at a point when there was great fury and misunderstanding and great tension between massive powers like America and Iran,'' he says.

''I've just become a new Muslim, and people are asking me questions, and I'm going, 'Hang on, I have to look at the scripture'. But that doesn't work, so I think I

fell for the trap.''

Whether he likes it or not, Yusuf knows he remains in a kind of suspension between two worlds. ''I'm kind of a looking glass in which Muslims can see the West and

the West can see Islam,'' he says.

And like any looking glass, the image can sometimes become distorted.

''People along the way have tried to cast me in another light or in another mould and I've never fitted it,'' he says. ''I'm out

of that box.''

CaTNiP

CaTNiP