It is high time the good people

of all faiths worked together

As we screech into another new year, I am having to grapple with the fact that many youngsters have never even heard the Beatles song, Yesterday. It’s an ominous sign of age creeping up and reminding you of your own mortality.

If that’s the case, how much hope can we bank on to imagine they would know that there once really was a guy called Cat Stevens who dreamt of transporting his generation to a better world with a song called Peace Train? Hearing anything more about this old "Cat" becomes even more remote when you realise that he decided to embrace Islam in 1977, when none of these kids were even born.

The next major ponderable impossibility would be for them to have been given enough accurate information about why he decided to jump off the friendly choo-choo and align himself to what is portrayed by some in the West as a religion that is hellbent on their destruction. How can we solve this paradox as we observe the blood-chilling news connected to the name of the faith he adopted as his own – Yusuf Islam?

Listening more closely to the "Cat" and his songs of the 1970s might have partially solved the riddle. When he stunned the music world by walking away from fame and money, all you had to do was to listen to Father & Son to hear the last words of the song say, “There’s a way and I know, that I have to go – away ...” But that still doesn’t really explain why.

Here comes the explanation: what people don’t know is that the actual station at which the earnest peace-seeking singer alighted, was in fact hundreds of light-years away from the [wild] world that sprouted around him following his entrance to Islam. After having reached the peaceful state of submission to God, emptying his ego and bowing his head, learning to pray and fast, it was only one year after his conversion when the Iranian Revolution suddenly shook the planet. This was followed soon after by the war in Afghanistan, the first Intifada, the Iran-Iraq War, The Satanic Verses publication, the Bosnian Genocide, the list of tragedies rolled on through to the September 11 attacks and up to the crisis we are facing today with the arrival of ISIL.

Now for the good news: having just attended the Reviving The Islamic Spirit Convention in Toronto, it was perhaps one of the most exhilarating reminders of the wonderful faith I had embraced before the negative storm of propaganda against Islam began to hail down upon us. Unfortunately, very few people know or have access to the teachings of this faith as so much attention is paid to the more radicalised elements of the Muslim community and receive an unfair percentage of the media’s valuable space.

Although Justin Trudeau, the Canadian prime minister, sent a video message of support to the event, there was hardly any other blip on the media's radar. Shame. It was truly refreshing listening again to some of the inspiring speeches of the scholars of this religion. But the metaphysical mountain of knowledge and wisdom of the scholars of the human heart are hardly seen or heard.

Belief ultimately should lead a person to be the most humane and chartable; the Last Prophet Mohammed said: “He is not a believer who goes to sleep while his belly is full while his neighbour goes hungry.” He also prophesied that there would be extremists of faith whose “words go no further than their throats”. The name given to radicals in Muslim history has always been the same: outsiders (khawarij). The Prophet maintained that the best of affairs lies in the "middlemost" of it, calling for justice, balance and moderation. And this was exactly what the convention was inviting to:the necessity of an “alliance of virtue”.

It is high time that the good people of the world, from all faiths and denominations work together to benefit mankind, through knowledge and good actions. The centre is where we can all meet; a place where we can stand high above the chaos caused by religious radicals and soldiers of destruction. One of the memorable sayings of a famous Muslim mystic, Rumi, comes to mind here: “Out beyond the ideas of wrong and right there is a field ... I’ll meet you there.” In that spirit, the words of my old anthem Peace Train also resonate: "Get your bags together / Go bring your good friends too / Cause it’s getting nearer / It soon will be with you.”

Call me Cat or Yusuf, I am an optimist – a believer cannot be anything else. Until that great train arrives, I hope that the new year will truly be one in which we can commit to our common humanity, and practice the heavenly teachings of true teachers and guides, many of whom I was honoured to meet in Toronto. Peace be with you.

[thenational.ae, 09. Jan. 2016]

Yusuf Islam on Cat Steven's 'journey to the peace train'

On the concluding day of the World Government Summit (WGS 2016), Yusuf Islam, more commonly known by his previous stage name ‘Cat Stevens’, held a key note speech at the GEMS Education Hall.

On the concluding day of the World Government Summit (WGS 2016), Yusuf Islam, more commonly known by his previous stage name ‘Cat Stevens’, held a key note speech at the GEMS Education Hall entitled “Journey to the Peace Train.”

During the session, the renowned former singer, songwriter and now turned philanthropist, described his personal journey of finding Islam and how it had a significant and lasting impact on his life and career.

Speaking about his heritage – being born in England and raised as a Christian, he reminisced: “What was going on outside the church was much more exciting. This was the big world. The world was geared towards one thing - making it. Making it was the idea of the ‘American Dream’ – the idea to get rich, to be on top, to stay healthy, and maybe even have a beautiful woman later on by your side, if you’re lucky.”

He then made the decision to do his best to become successful. Citing ‘the Beatles’ as a great example of successful songwriters ‘making it’ he decided to embark on a similar journey. He developed a great talent for creating catchy songs and achieving big hits.

“I then went on the road and that was when the beginning of my career really began,” he explained. “On the road, I often found myself staying up late, partying, smoking cigarettes, consuming alcohol to the point I couldn’t take it anymore. I then contracted tuberculosis. After being admitted to the hospital, I became aware of mortality, and started realizing the certainty of death.”

It was from this moment on that Stevens created a new catalogue of songs that reflected his new perspective on what he wanted his music to be about. While performing on the road, he began to look for answers, and read books of different faiths and religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, numerology and much more. He said, “Before death comes, I wanted to know what was going to happen. I needed to know.”

He then composed some big hits related to his search and the events that occurred around him, such as ‘Miles from Nowhere’ and ‘Peace Train’. “While on tour, there was the Vietnam war. Then we were suddenly entering the space age and now the moon was the new battlefield.” He explained that while he was making all these records, peace did not come with it, and that he still felt unfulfilled.

Then a major turning point occurred in 1975, when Stevens visited his record chief’s house in Malibu. “The water was looking good that day, so I went for a swim. As I went into the waves, I began to get tired and exhausted, and didn’t realize that the current was pulling me out of the land - and not any closer. At that point I thought it could be the end. At that point, I called to God, and said if you save me I’ll work for you. Then the waves pushed me back on land and I was alive. I thought what next? Where do I go?”

He then found his answer a little while later, when his brother gifted him the Quran from his travels. Stevens said: “I’m an open minded person. As I read the Quran, one of the biggest things that struck me was the clarity in the first commandment. I thought to myself, so that is what it is and means. Religion wasn’t as alien as I was led to believe. The Quran talked about how humanity is a family, how it was just one race and one family with no distinction. I knew this was a book from God.”

Fast-forwarding to today, he explained that after becoming a Muslim, he started realizing the challenges facing Islam around the world and got involved with education and set up Islamic schools.

In his concluding remarks, he shared a key message - about the need to share knowledge like the Quran, and how this was an opportunity for all. He stressed: “When humans reach a level of comprehension with each other, there are no battles and no battleground. It is important that we share our learning. And to share this knowledge, let us use the advantages of mediums like technology - while maintaining good character.”

The World Government Summit has convened over 3,000 personalities from 125 countries. The summit concludes today (February 10) at the Madinat Jumeirah in Dubai.

[emirates247.com, 12. Febr. 2016]

„Die Türkei hat getan,

wozu die Welt nicht in der Lage war.

Sie hat Großzügigkeit bewiesen.“

Während der Veranstaltung

Konya: Tourismushauptstadt der islamischen Welt

dankte Yusuf Islam in einer Rede der Türkei

für ihre Haltung gegenüber den Flüchtlingen.

Während der Veranstaltung Konya: Tourismushauptstadt der islamischen Welt dankte Yusuf Islam in einer Rede der Türkei für ihre Haltung gegenüber den Flüchtlingen. Islam erklärte:

„Die Türkei hat getan, wozu die Welt nicht in der Lage war. Sie hat Großzügigkeit bewiesen.“

Yusuf Islam, der als Cat Stevens Musikgeschichte schrieb und nach seinem Übertritt zum Islam seinen Namen änderte, erklärte, dass beim Thema Syrien die Türkei etwas getan habe, wozu kein anderes Land in der Lage gewesen sei – sie habe mit all ihrer Großzügigkeit den Flüchtlingen ihre Tore geöffnet.

Yusuf Islam sagte auf der Präsentationsveranstaltung von Konya: Tourismushauptstadt der islamischen Welt, an der auch der türkische Ministerpräsident Ahmet Davutoglu teilnahm, dass es große Unterschiede zwischen der Türkei zum Zeitpunkt seines Übertritts zum Islam und der heutigen Türkei gebe.

Der Künstler betonte, dass die Türkei in ihrem Licht weiterhin erstrahlen werde und fuhr fort:

„Die Türkei ist wie ein Blumengarten. Bevor ich mit dem Koran anfing, bekam ich ein Buch mit Gedichten von Maulana Dschalaladdin Rumi geschenkt. Und eben diese Gedichte Rumis stellten meinen ersten Schritt dar. Diese Gedichte öffneten mir das Fenster zu der Schönheit des Islams. Von jenem Zeitpunkt an weitete sich meine enge Welt und ließ mich mit der Wahrheit allein.“

Yusuf Islam wies darauf hin, dass die Menschheit von heute den Frieden mehr denn je brauche:

„Beim Thema Syrien hat die Türkei getan, wozu kein anderes Land in der Lage war. Sie hat mit all ihrer Großzügigkeit den Syrern ihre Tore geöffnet. Leider reden sie von etwas namens Menschenrechte. Menschenrechte sind so wertlos. Die Menschen, die zurzeit sterben, sind völlig wertlos. Man muss dazu sagen, dass auch Deutschland wie die Türkei die Flüchtlinge aufgenommen hat. Auch ihnen sollten wir unseren Dank aussprechen.“

[nachrichtenxpress.com, 23. April 2016]

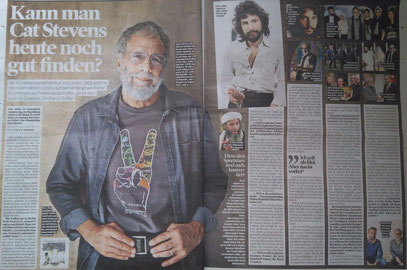

Cat Stevens interview exclusive

If you got the chance to interview Yusuf Islam what would you ask him? Maybe you’d want to know about his life as Cat Stevens, the artist who in the 1970s sold millions of albums and was without doubt one of the biggest artists on the planet? Or maybe you’d question why he turned his back on stardom, converted to Islam, sold all his guitars, and began a completely new life that seemed totally at odds with everything that had gone before?

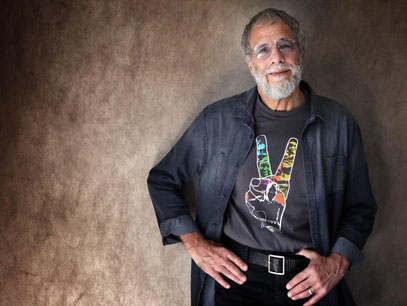

Then again, perhaps you are a Muslim and it’s only Yusuf Islam the charity worker that you have ever known, via his educational spoken-word CDs and his faith schools. You might be more interested in why he is once again touring as Cat Stevens and now seems comfortable with his old life – or should that be his old, old life?

The point being, he has many different personas and people hold strong opinions about them. I’ve had plenty of time to consider all those viewpoints.

It’s taken five years to pin Yusuf down to an interview – mainly because he is constantly juggling all these aforementioned commitments. But now, finally, the timing is right. It’s Ramadan and, in the spirit of the Holy Month, he has just released a song “He Was Alone” to highlight the plight of refugees in Europe. It’s a subject he feels passionate about, so he wants to talk.

There was a lot to discuss, which we did over two interviews in Dubai, where he has a home. Further insights came from trips to meet his team at their music studios and even from shadowing him for a day of press interviews in London. His book, Why I Still Carry A Guitar (WISCAG) also helped set the record straight.

It’s been a lengthy journey, though of course not half as far as the road he’s travelled. So let’s start at the beginning…

***

Well I hit the rowdy road / And many kinds I met there – “On The Road To Find out”, Tea For The Tillerman, 1970

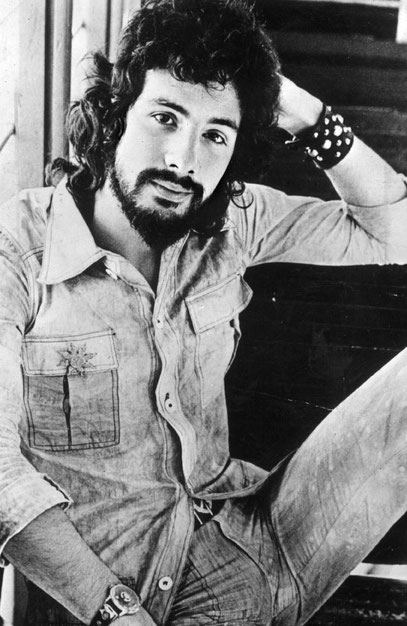

His name was Steven Demetre Georgiou, son of a Cypriot father and Swedish mother, raised in a flat above the family restaurant in London’s West End district. The year of his birth, 1948, meant his adolescence coincided with the explosion of youth culture in the 1960s. Britain’s capital city was the epicentre for music, theatre, art, fashion, youth, rebellion and profound social change – and all of it was a stone’s throw from his doorstep.

“I’d run from home from school and sneak into these strange warehouses where they’d be building the scenery for shows, and in and out of picture houses and

theatres,” he says today, all these years later. “It was so free spirited and open. I didn’t have to choose my identity or be anything. I could be

anyone.”

He describes the music, and the now legendary bands he saw at the 100 Club near his home as, “a continuous and ecstatic joy ride for those who experienced it. There was constantly some new discovery; it was like we were finding life on Mars. The songs were coming at you, one after the other, everyone of them a masterpiece.”

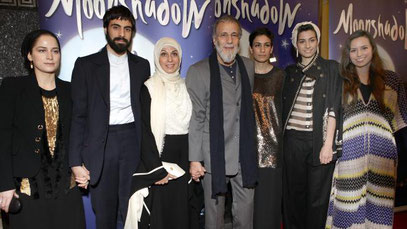

He’s regaling me with these stories over lunch at a low-key Chinese restaurant near his home in Dubai. His son, Yoriyos, who helps run their business and charitable ventures, is sitting with us and they’re both unfailingly polite, both to myself and the staff. No one recognises him, though most people here – the Filipino waiters, Chinese chefs and Arabic diners – would know at least some of his songs, even if they don’t spot the writer in their midst.

I’d wondered how happy he’d be talking about his distant past, but he seems to be at a place in life where he’s happy to look back with gratitude at the memories – especially when I ask him if the whole “Swinging Sixties” could really have been that good? “Ah, it was great,” he responds with the laugh of someone who knows what the rest of us missed.

Between mouthfuls of food, he talks about how his early attempts to play the guitar and the songs he learned to write with it. In 1966 he changed his name to Cat Stevens, got a record deal and wrote his first hits including “I Love My Dog”, and “Matthew and Son”, the title song from his debut album that went to number two in the UK. Over the next two years he had a run of hits, and played with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Englebert Humperdinck.

One thing you couldn’t do, even then, was pin him down to a genre or scene. “There was this record store across the road and they were always ahead of everyone else with their stock,” he remembers. “You’d hear a Scott Joplin song and be like, ‘Wow what’s that?’ Music was everywhere and I was picking up all kinds of tones, tastes and delicacies. Spanish, Russian choral or Armenian or electronic... I listened to everything.”

For this reason he felt more comfortable as a solo artist, and his eclectic tastes reflected a restless nature (it’s perhaps no coincidence that he was on the same record label as a young David Bowie). So although he loved what was going on around him, Yusuf also describes himself as more of an outsider, and his lyrics went way beyond the usual boy-meets-girl scenario. “You want to be with the most beautiful girl in the world, who loves you just for who you are,” he says wistfully, “but I didn’t know who I was, so, how could anybody do that?”

It was obvious, even in those first songs, that his search was about more than romantic love. He was asking some pretty big questions of himself – and about life in general.

I wish I could tell, I wish I could tell / What makes a heaven what makes a hell – “I Wish, I Wish”, Mona Bone Jakon, 1970

There would soon be plenty of time to stop and think about the bigger picture. Stevens’ hedonistic “joy-ride” was stopped in its tracks when tuberculosis almost killed him in 1969. He went from being a teenage pop star with the world at his feet, to facing a year-long recuperation from the disease.

So while the Sixties roared on, and bands like The Who could blithely proclaim, as only the young can, that they hoped they would die before getting old, Stevens was suddenly confronted with death as a very real possibility. Lying in a hospital bed in the countryside away from London, he thought deeply about his religious background – he’d been to a Catholic school – and also began exploring Buddhism and meditation. “It was a stop sign that made me reassess everything,” he says when I ask how big an impact the illness had on his life. “It also re-emphasised something I’d always had within me, which was the search for peace, where you’ve found a place in this universe which is right for you. And that goes along with finding out more about your own identity.”

Many people naturally want to understand

how an iconic long-haired hippy pop star that sang

and embodied their dreams ended up a muslim,

prostrating in prayer five times a day

and abandoning drinks, parties, adoration and applause

Yusuf Islam, WISCAG

As well as taking stock of his life over those long months alone, Stevens wrote dozens of new songs. They were simpler guitar-orientated pieces that he describes as being “full of spiritual enquiries, openness and childlike honesty” and they were perfect for the early 1970s market, where singer-songwriters dominated the charts. Backed by the legendary Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, the album Mona Bone Jakon was released in 1970 followed six months later by the record that would make him a worldwide star, Tea For The Tillerman, which included “Father and Son”, “Wild World”, “Where do the Children Play?” and “Hard Headed Woman”. Blackwell described it as “the best album we’ve ever released” which was high praise considering he managed some of the most critically acclaimed artists of the era. Teaser And The Firecat came next, with “Peace Train”, “Morning Has Broken”, and “Moonshadow” all becoming instant classics.

But all the resulting wealth and adoration couldn’t quieten the questions that nagged at Stevens. “Looking back into my albums, a person would see quite clearly that within me was a fluttering soul that could not settle down,” he writes in WISCAG. “I was still restless and empty inside.”

On this boat called ‘near and far’ / To be what you must, you must give up what you are – “To Be What You Must”, Roadsinger, 2009

It took another near-death experience for Stevens to find his true spiritual path. He was in America, swimming one morning in the ocean, off Malibu Beach, and didn’t realise until it was too late that a strong current was carrying him away from land. In WISCAG he describes what happened next: “I realised there was no other way and called out, praying from the depths of my sinking heart, ‘Oh God, if You save me I’ll work for You.’ At that moment a gentle wave pushed me forward and I was able to swim back. That was my moment of truth.”

What he didn’t yet know was that Islam would be that path to God. It was his brother, David, who bought him a Qu’ran, knowing that his younger sibling was interested in spiritual books. Stevens read it over the course of a year, but it wasn’t until he got to the story of Joseph (or Yusuf in Arabic), that something resonated like nothing had ever done before. He knew what he needed to do.

In 1977 Cat Stevens walked into London Central Mosque in Regent’s Park to declare his belief and enter the Ummah – the nation of faith. He has never knowingly missed a prayer since then. Quickly realising that he couldn’t reconcile his new life with the music business, he put out one last record, Back To Earth, as Cat Stevens, before taking the name Yusuf Islam on July 4, 1978, and starting again.

I would have been an utter hypocrite if I discovered what I did

and then walked away from it.

That would’ve been a betrayal of everything I’ve ever stood for

It cannot be emphasised what a totally new experience this was for Stevens. This was before world events brought Islam into focus, and the religion was still relatively unknown in the West. He’d had never even met a Muslim until the first day he became one. As Yusuf, he would soon marry a Muslim girl, Fauzia Mubarak Ali, start a family (he has five children and seven grandchildren), grow out his beard, adopt a more Islamic style of dressing and donate his guitars to charity. He also decided which of his songs were haram or halal, keeping the royalties only from the latter category, then threw himself into learning Arabic and starting charitable and education ventures. I ask how he coped with such a profound transition and he shrugs his shoulders. “Once you’ve decided to jump in the water, there’s not much else to do apart from learn how to swim,” he replies.

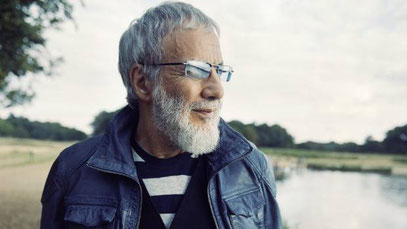

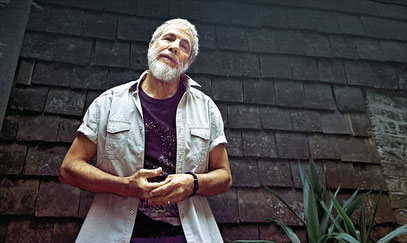

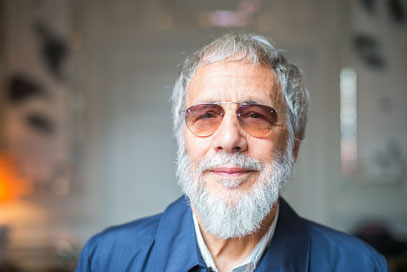

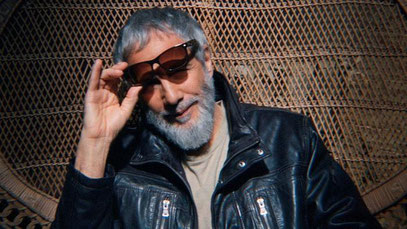

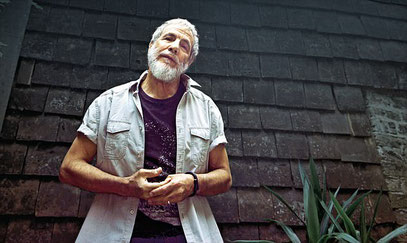

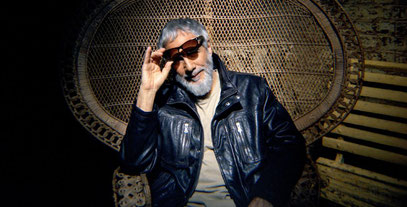

Today, in the Chinese restaurant in Dubai, his beard is trim and he’s dressed in the western clothes he re-adopted a long time ago now. His clothes are modest and age-appropriate, though the vintage aviator sunglasses and stylish jacket are subtle hints that the pop star of yesteryear has not completely left the building.

Discussing the move away from his old life he says he doesn’t regret any of it, apart from the confusion it caused to his genuine fans. Yet he’s adamant that there was no choice. His music had always been about finding truth and he couldn’t live a lie once he’d found his path. “I’ve never really had a profession other than expressing myself, and I would never want to misspend that responsibility. That’s why I walked away from the music business,” he says, deadly serious for a moment. “What I was looking for wasn’t just a mirage, it was true. I meant it. And I would have been an utter hypocrite if I discovered what I did and then walked away from it. That would’ve been a betrayal of everything I’ve ever stood for.”

You know I used to weave my words into confusion / So I hope you’ll understand me when I’m through – “Dying to Live”, Tell ’Em I’m Gone, 2014

Yusuf says he loved this period in his life, discovering a new community, starting a family, learning about himself and his religion. But the world was changing. One year after converting, the Iranian Revolution sent shockwaves around the world and Yusuf laments how Muslims in the West felt like they suddenly had to choose sides. Almost overnight, a benign disinterest about Islam turned into something darker and more immediate. “A wall was being built around us;” he writes in WISCAG. “We were thrown into the shadows of a long dark night.”

One disaster followed another: the Iran-Iraq war, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the abandonment of the Palestinians, famines, floods and earthquakes, the Bosnian war, 9/11... The list of calamities goes on, brutal and dark and it would have profound implications for Muslims in general and Yusuf personally.

People calling me Cat Stevens? That's OK. It's just a hashtag

Because Westerners didn’t know much about Islam, Yusuf found himself becoming a de-facto spokesperson for a religion he was only just discovering. In the long run this would be a useful platform for sharing knowledge and ideas, but it would cause huge problems in the early years, when he was still finding his way. This came to a head in 1989 when he was asked to explain his position regarding the fatwa by the Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran on Salman Rushdie after the publication of his inflammatory novel, The Satanic Verses.

Yusuf says his responses to the barrage of questions about whether he supported the fatwa were deliberately twisted – especially in one painful encounter with a QC in a live television debate. And when he did release a statement regarding his position, certain lines were taken out of context from the message he was trying to convey. The episode cast a long shadow, though his position has long been clear, as he re-iterates in WISCAG. “The truth of the matter is that I never agreed with the fatwa, in fact, I firmly believe it went against the basic injunction in Islam which forbids the taking of life without just right – lawfully – part of due process in maintaining law and order within society. Never did I say ‘kill Rushdie’ or believe that Muslims were morally or duty bound to take the law into their own hands.”

For that reason, it seems pointless today to rake over old ground again. There will always be critics who choose to rely on YouTube snippets, rather than read his considered responses. It seems more appropriate to ask how the position he was in – straddling Islam and the Western world – made him feel in general. “I think I was affected by the people around me,” he says of those years living and working with his Muslim brethren in north London. “A lot of them had left their countries, just trying to save their skins, and weren’t being accepted. And then you can’t help but be affected by the catastrophes happening in the rest of the world; it was all pretty dark. There wasn’t much for many Muslims to smile about and that must have rubbed off on me.”

The world is still a difficult, messy place in which to live, but Yusuf’s outward manner is very different today. Although he still wants to talk about the problems of inequality and injustice, in general he just seems a lot looser than perhaps he once would have been. When I ask him what changed his perspective he says what many parents or grandparents would understand: that having children lightened him up again. “You can’t be that serious. Well, maybe at the beginning, but then you’ve got to learn how to be a father and learn to ease off, because freedom, I think, is God given, so you have to respect the fact that everybody has to get through this learning curve on their own, with a bit of help guidance and advice, but in the end everybody’s doing it on their own.”

Being a spokesperson for his faith is a burden he also seems more willing or able to shoulder these days. Although he is quick to point out that he doesn’t have the answers – “I am not seeking or asking anyone to follow me, or my various conclusions, but only to look within themselves at the signs of the eternal truth,” – is how he describes it in WISCAG, he’ll happily discuss Islam’s proud history as a culturally progressive force, a fact he thinks has been deliberately downgraded in the West. He’ll quote Rumi’s beautiful mystic poetry and reemphasise time and time again the peaceful, inclusive nature of his religion. Basically, he seems more secure with the path he is on , the wisdom he’s gained over the decades and the opportunities his music and faith have given him to help others.

I have dreamt of an open world / Borderless and wide / Where the people move from place to place/ And nobody’s taking sides – “Maybe there’s a World”, An other Cup, 2006

To many people, Yusuf will always be remembered for being the pop star who became a Muslim. But what will arguably be a far bigger legacy, albeit one that has often gone under the radar, is what he has done with that platform. A key tenet of Islam is charity – zakat – and he was very active from the beginning in this regard. As well as founding the first British Muslim government-funded schools in London he started his own charity, Small Kindness and the Yusuf Islam Foundation. For many years this, along with education, was his fulltime occupation.

Yusuf is animated when he talks of how compassion can literally be a game-changer for humanity. “The only way to communicate, share and expand is through human contact with those who don’t have as much as others, which brings you back to the great rules of life,” he says. "There is a saying in Islam, “Love For Your Brother What You Love For Yourself”. Jesus said, “Do to others as you would have them do to you”. And this runs all the way through to the Declaration of Human Rights, which is about good neighbourliness. Well, hey, where did that go?

Parts of Europe are locking the doors, due to that lethal disease of prejudice, and a lot of it goes back to education. So charity and education are always going to be the main areas of work that I love to be engaged in.”

For this reason he refuses to bow to cynicism or despair, even having just returned from a refugee camp in Turkey. “There is a lot of injustice in the world,” he says, “but there’s also an optimism that’s like the ocean. It renews itself if you just stop interfering with nature.”

It’s also the reason he’s doing this interview with Esquire – to raise awareness for his beautiful new song “He Was Alone” aimed at raising awareness of the refugees – particularly the children – desperately trying to survive the journey to Europe.

In all the emotive discussions about refugees, it’s an overlooked fact that an astonishing 10,000 children have gone missing since the Syrian crisis began, according to the EU’s criminal intelligence agency.

“One of the biggest crimes today is reductionism,” Yusuf says of his inspiration for the song. “We talk about ‘millions of people’ as if it’s just a figure... we’ve lost the human contact.” The moving video for “He Was Alone” focuses on the story of an actual refugee, a twelve-year-old boy, and his journey from Syria to Turkey. It was due to be played in front of world leaders and other influencers at the end of May at a UN-backed World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul; men and women who have the power to shape policy in Europe.

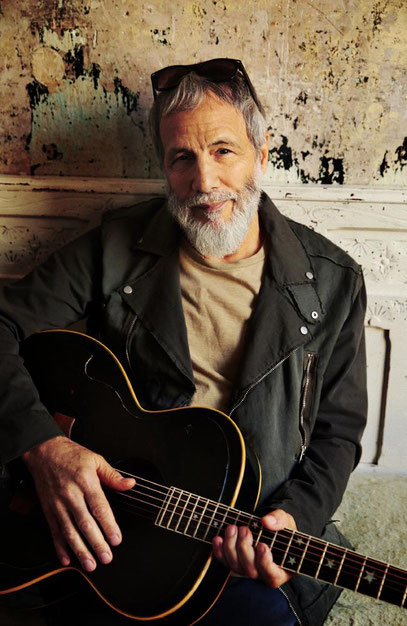

This is the power that music has given him – the ability to share, communicate and inspire through music. Which brings us to the $64 million question: why did he come to pick up the guitar again, 25 years after renouncing it as being incompatible with his faith?

Then a stranger sang / The voice like the wind / Then the hails began to sing / Welcome in – “Welcome Home”, Roadsinger, 2009

For many years Yusuf erred on the side of caution regarding the role of music in Islam. He did not play or sing, on the advice that it was probably incompatible with his faith. This viewpoint gradually softened over the decades as he learned of the less restrictive view of many other scholars. “Islam does not forbid what is good and meaningful in art and music,” he writes in WISCAG. “It simply does not sanction what is vile, mindless or vain”. To that end, he set up Mountain of Light in 1994, a charitable organisation and studio dedicated to promoting Islam. His spoken word album, released in 1995, The Life of the Last Prophet, was a worldwide hit in many Muslim countries, which showed that he still had an ability to connect to audiences.

“The Little Ones” was his response to the war in Bosnia, and it led to an album I Have No Cannons That Roar in 1998, though he wasn’t actually playing on any of these compositions. A is for Allah followed in 2000, which led to more educational CDs. In 2001 he opened an office and then a studio in Dubai to produce more children’s songs.

In 2002 Yusuf finally picked up the guitar again, after Yoriyos brought one to their house in Dubai. This would once have been a cause for consternation, but instead of scolding his son he did something else. One morning, when everyone else was sleeping, he picked up the guitar and placed his fingers on the fretboard. He quickly found a C and D chord, thought for a while and then remembered the correct voicing for F. And there he sat, playing as a beginner, the guitar full of possibilities. From this moment the music began to flow again and has yet to stop, which he thinks is because “it was like going back to having nothing to lose... It’s back to when you were a kid.”

Another series of marker points led him back to writing and performing on a permanent basis. He wrote “Indian Ocean” for victims of the 2004 tsunami and went to Indonesia to distribute aid. And, in what was perhaps the perfect example of his more humorous side reasserting itself, he turned the very troubling experience of being refused entry to the US in 2004, thanks to the FBI mistakenly placing him on a no-fly list, into a song that poked fun at the ordeal. “Boots & Sand” was catchy, subversive and funny, with Dolly Parton and Paul McCartney, who are both fans, proving backing vocals, and Bob Dylan’s son, Jesse, directing the video.

He released his first full album in almost 30 years, An Other Cup in 2006, followed by Roadsinger (2009) and Tell ’Em I’m Gone (2014), and also wrote a musical, Moonshadow. He’s also just finished another album, this time with his old producer Paul Samwell-Smith and guitarist Alun Davies who worked on his most famous early material. This one revisits some early material, including “Mighty Peace” and “Northern Wind (The Death of Billy the Kid)”, of which he is especially proud, as well as some standards and new compositions. He’s clearly delighted to be back with his old comrades, rediscovering the unique magic and longevity of those songs.

This brings us to a big question I’d asked myself about Yusuf Islam: How do you explain the enduring power of his music? (I should confess to a longstanding interest in this regard. I’m speaking now as a journalist who has had a sideline playing music in bars for the past 20 years, and I can report that the likes of “Wild World”, “Father and Son” and “First Cut is the Deepest” have always been among the most requested songs – and not from any one demographic either. This has often led me to wonder why some songs just never lose their hold on people.)

In an anonymous-looking Turkish restaurant near Satwa,the setting for our second interview, the man who wrote these classics humbly sips his tea and thinks about the question. “It’s got to be a reflection of people’s own experiences or their emotions,” he eventually says. “A song can feel like it was written for you, and it’s wonderful to be able to reflect things that they perhaps couldn’t explain in any other way.” Ask how he managed to capture those emotions, he puts down his cup and pauses again. “When you ask me today who wrote those songs then I have to really ponder, because I don’t know.”

Like many other artists, he says that most of his best-known work almost seemed to write itself. “In the early days you’re not really thinking about it, you’re in the middle of everything. But on reflection it must be a bit like when a scientist unravels some mystery, DNA or whatever, and he’s discovered what was already there and he’s, like, ‘Wow, I’m the first to see it!’. And when you write music you’re the first one to hear it. So you’re very lucky... But it doesn’t mean you wrote it.”

I tell him about a phrase I’d heard a couple of days before, “music is the sound of feelings” and how I immediately associated it with his songs. “Well, music is the straightest way to get to the heart, and the heart is where our conscience lives,” he agrees. “And it can be manipulated sometimes or used for titillation, like a lot of music today, or it can strike another chord that makes you stop and think.”

He jokes that, back in the day, he regretted the fact that other people’s music made an audience dance, whereas his songs made them sit down and ponder, but now he realises that is a good thing. And to return to the purpose behind his new release “He Was Alone”, that is a powerful tool. “It’s an example of how music has enabled me to get back to social commentary, you know, back to protest,” he says.

And here’s where we get to the most fascinating part of the story: the idea that Yusuf’s whole journey has been moving and changing so that he can get back to where he started.

Life is like a maze of doors and they all open from the side you’re on / Just keep on pushing as hard as you can / And you’re going to wind up where you started from –

“Sitting”, Catch A Bull At Four, 1972

The more I looked at the journey of Yusuf Islam in the months, years, leading up to our meetings, the more it became clear that the question most people ask of him, or rather Cat Stevens – namely, why did he change? – is the wrong way of looking at his story. Study anything he has ever written and you realise that the journey has been about staying true to an ideal he formed at a very young age, rather than breaking away from it.

There are countless clues or markers that point to the direction he was travelling in, even if we could not know it at the time. Yusuf has been thinking about this a lot lately, as he’s working on an autobiography, and says the process of rediscovering his origins has taught him a lot about where he is today. For instance, the region his father’s family hailed from, Cyprus, was once part of the Golden Crescent of the Muslim world.

“...And so you think, Oh, maybe I am from the Middle East after all,” he says with a laugh. “It’s great to make these discoveries. You re-establish this context and life becomes this clear road again. It’s a really interesting process. I recommend it to anyone, no matter what kind of life you’ve had.”

He also discovered that the small town in Sweden, near Gävle, where his mother came from, was also the birthplace of Joe Hill, who went on to become a labour activist and songwriter in America at the start of the 20th Century. He’d later be sung about by many of the folk singers of the early 1960s who inspired a young Cat Stevens.

Yusuf’s book will also include wonderful vignettes such as Jimi Hendrix squirting a water pistol at him from behind the curtains while he was singing “I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun”. The two were on tour together when Hendrix first burst on to the scene and he laughs again at the memories. “I should have done the same to him when he lit his guitar on fire,” he laughs.

One of the most revealing clues to his future journey, as revealed in the book, is that the first proper song he ever wrote was called “Mighty Peace”, which basically delineated his path from the very beginning. He’s re-recorded it for the next album, in recognition of the place he was at both then and now.

I ask if he agrees with this assessment of his career going full circle to answer the questions he’d posed in his songs at the beginning. “I’ve always carried the feeling that somehow there is a plan for me,” he affirms. “Discovering Islam was one of the big discoveries of that plan, because I had written so many songs that almost described where I was going, but in more generic terms. And then when I dropped the guitar that also felt right at the time.”

Recently he got a kick out of discovering Ziryab, an 8th Century Muslim poet and musician who introduced the oud to Spain (which later led to the invention of the guitar) and also brought the influences of North African music with him to Europe. The knowledge that this must have been part of the musical journey that led to the blues and rock and roll is not lost on Yusuf.

Everything in the journey, it would seem, turns out to have happened for a reason.

So on, and on I go / The seconds tick the time out / So much left to know, and I’m on the road to find out – “On the Road To Find Out”, Tea For The Tillerman, 1970

Today when he releases new music, Yusuf Islam tends to just use the moniker “Yusuf” on the promotional material. It’s shorter, snappier and has fewer connotations for the more wary among his western audience about where he is coming from. But he also doesn’t mind putting Cat Stevens somewhere on an album cover or tour poster if it helps identify him to his audience.

Some people still struggle with this not very complicated dualism. I sat in the BBC studios in London a couple of years ago while the Radio 2 DJ, Simon Mayo, spent the first few minutes of the interview trying to establish Yusuf’s proper title. The conversation went something like this:

What should I call you?

Well, my name’s Yusuf Islam

But some people still call you Cat Stevens...

That’s fine too

Which do you prefer?

Well, my name’s Yusuf

So either?

Whatever you’re comfortable with...

And so it went. But this was a revealing, if a little torturous, conversation. People want to know what box Steven Demetre Georgiou / Cat Stevens / Yusuf Islam fits into. But in truth, how many

of us do fit into one mould? “Well, some of us are dads; we’re brothers, sisters, friends; we have names and nicknames,” he says when I remind him of the

encounter in London.

“Cat was a very appropriate name at the time; it was part of my independent personality, but then Yusuf was the key to me because I loved the name Joseph.” His last record says “Yusuf” on the cover, and in smaller letters on a sticker, “Cat Stevens”. “That’s okay,” he shrugs. “It’s just a hashtag.”

He’s telling me this over a very late lunch, shortly before leaving for dinner with one of his daughters. He’s patiently endured a photoshoot on a hot May afternoon in Satwa, and now we’re cooling off indoors along with Yoriyos. It’s our last interview before Yusuf goes back to Europe to launch “He Was Alone”, so it seems appropriate to finish by asking about his legacy. He thinks first, choosing his words carefully, perhaps mindful, as always, of the need for humility in his answer.

Or maybe he’s just too busy to have thought about it yet.

“I hope the messages of my songs will continue to be relevant, which they seem to be today, so that’s important,” he replies. Then we talk about the faith schools he helped established in London, of which he’s clearly proud. “We’ve had a breakthrough where Muslims get equal treatment in the UK, at least in education.” He also discusses the unity of thought and belief that he found in Islam and hopes this will be more widely publicised in future. Amid the gloom of recent times there are reasons to be optimistic. London just elected a Muslim mayor, Sadiq Khan, who has promised to work for everyone. “We need more of it,” Yusuf says.

Finally, he wants his audience to understand why he left the guitar and why he eventually picked it up again – because he had to stay true to the ideals he’d always sung about. “It’s about commitment. I never sold out to anything other than God. The only one worthy of true commitment.”

But right now he has more immediate concerns other than thinking about legacies. His daughter phones to remind him that they have a dinner date, and from the sound of their conversation she wants to know why he is already in a restaurant. He assures her that, no, he hasn’t spoiled his appetite, tells her he’ll be there shortly and then apologises to me that he has to leave.

As we wait for the bill, watching the waiters prepare for the evening crowd, I ask what he learned from helping out at his father’s restaurant all those years ago back in London. “That you should always tip the hard-working staff,” he laughs.

So we leave some change and make our way outside into the rush hour. Yusuf offers me a ride home as he’s going in my direction, and he wants me to hear a freshly done mix of “Northern Wind” that he seems thrilled with.

I’m happy to report that it feels like a quantum leap for his sound. It’s like everything you’d hope for from a latter-day Cat Stevens song, thanks to its poignant story and a beautiful, rich production. But best of all there is the voice. Thanks to suffering from a cold in the studio, Yusuf dropped the melody by an octave and his vocals seem to have acquired a new gravitas that helps convey his message. As we drive I hear the wisdom of a 50-year search for meaning; the sound of an artist deep into his journey. It is, in my opinion, one of the best things he has ever recorded and an emphatic case for everything he has ever done or said.

For our sakes, thank goodness he went away to find himself and his faith – and then came back to share the fruits of those labours. Although for him, of course, he never really went away. He just got closer to where he was always heading.

[esquireme.com, 22. Juni 2016]

Cat Stevens' Peace Train pulls into

New Zealand for just the second time

There might never have been a Cat Stevens if it weren't for Jane Fonda.

The Beatles, the Yardbirds and even the Monkees also had a hand in his creation - though not necessarily in the way you might think.

Now called Yusuf Islam - a name he adopted a year after he became a Muslim in 1977 - Cat Stevens was born Steven Demetre Georgiou in 1948, to a Greek Cypriot father and a Swedish mother living above their family restaurant in London's West End.

In recent years he has undergone another (minor) name change, dropping the surname Islam from his stage persona to become simply 'Yusuf' - a decision made mostly due to the journalistic habit of referring to people by their last names.

"Reading things like, 'Islam says…' worried me," he says on his website.

"It was not appropriate for pop-journalists to write things like, 'Islam's new album'."

As for Cat, that was only supposed to be a temporary thing - a stage name to counter the fact that he couldn't imagine anyone asking for an album by Steven Demetre Georgiou.

"Well, there were the Monkees, there were the Yardbirds, there were the Beatles - and I figured that animals were like, in, you know?" he laughs. "Also, there happened to be films around at the same time like Cat Ballou, What's New Pussycat? - cats were flying at me all over the place. So I just said, this is it.

It was only temporary until I thought of something better, but it ended up on the record label and it's been stuck there ever since."

It's a strange thing to be interviewing Cat Stevens - hereafter referred to as Yusuf - not least because I'm at first unsure of just what are appropriate subjects to talk to him about.

While he hasn't exactly shied away from interviews since his return to the world of 'secular' music in the mid-2000s, it's hard to shake the sense that Yusuf's Cat Stevens days are somehow off-limits - despite the fact he's been playing old hits like Peace Train and Moonshadow again for years, as he did on his last (and first) visit to New Zealand in 2010.

Maybe it's the way the internationally renowned singer-songwriter - at what could be called the height of his fame - so abruptly quit the music business altogether, converting to Islam, changing his name and releasing one final album as Cat Stevens before auctioning all his guitars for charity and devoting his life to philanthropic causes around the world.

Any concerns I might have had are almost immediately dispelled when I get him on the phone however - Yusuf seems perfectly happy to talk about everything from the weather and Facebook to the inspiration behind Matthew And Son and the reasoning behind his return to music.

In Sydney promoting his upcoming Australian tour - he'll be there from November to December before coming here for three dates in Auckland, New Plymouth and Christchurch - Yusuf comes on the line after a vaguely confusing exchange between myself and his son Yoriyos, who I at first mistook for the man himself (all the while marvelling in my head at his miraculously youthful-sounding voice).

Like his father, the son is a singer-songwriter - Yoriyos is actually another stage name; he was born Muhammad Islam - and is also the person responsible for bringing Yusuf back to the guitar after a quarter-century absence.

It was 2002 when the then-teenage Yoriyos brought a guitar home to their house in Dubai - and late that night when his family was sleeping, Yusuf picked it up and tried out a few chords.

"I didn't have a guitar for many years, because I'd just got ridden of them all," says Yusuf, still sporting a surprisingly distinct London accent. "And then when I got the guitar back I started to play, and at that point, immediately I started to write.

"The first song that I wrote actually hasn't been released yet, but one day it'll come out. It's a very moving song - very moving - and it was kind of like the inspiration came back to me."

Yusuf not only has a knack for moving people with his music - the lyrics to Father And Son rarely fail to bring a tear to my eye - but for me there's always been something about his songs that also seems to make a deeper connection with the listener.

The summer I left school my friends and I absolutely thrashed the 1990 release of The Very Best Of Cat Stevens, listening to it alongside albums by more (at the time) contemporary bands like Sublime and Red Hot Chili Peppers, and I wanted to know if Yusuf had any idea why his songs continue to endure 30, 40 and now even 50 years after they were written?

"I think the spirit of the counter-culture sort of movement that I belonged to, and I contributed to, still stands relevant today to many kids," he reflects.

"Growing up in the world today, it's becoming harder and harder to find your identity I think - because everything is corporate stamps. You've got your Facebook, but even on that you become a trademark yourself - of your own image.

And people change, so I think I represent someone who went through those changes - it's that I think that resonates maybe."

The changes have continued for Yusuf over the years - these days he even admits that his sudden departure from music might have been a somewhat "radical and over-zealous reaction" to his newfound faith.

And while he acknowledges that there are those in Islam who may disagree with his decision to return to the music that made him famous, his own standpoint seems to have mellowed considerably.

"I think what I'm doing by singing again is kind of bringing people back to the basic human heart of it all - because that's what it's all about," he says. "Unfortunately politics really does a nasty business in separating people. Especially these days, we can see politicians make a whole career out of it - you know, out of making divisions and building walls and all sorts of things.

So it's great to be able to, in a way, represent a bridge between the cultures that I represent. By the way, recently I wrote a book - a short book - called Why I Still Carry A Guitar, so I'm also trying to explain to the Muslim community, 'Hey, that's why I'm up on stage' - because I think it's a great way to communicate, a great way to unite."

[stuff.co.nz, 02. April 2017]

Yusuf Cat Stevens talks on

sharing melodies with Coldplay and borrowing them from Beethoven

Is it a coincidence you were in Australia at the same time as the announcement of your 40th anniversary tour?

We are partnering with some animators here in Australia for a children’s series based on my songs.

Is the series a reimagining of the Moonshadow musical you staged in Melbourne in 2012?

The Moonshadow experience was very, very enlightening for me because I had to get it out of my system, I wanted to see this thing on stage.

I realised then perhaps people need to get to know the fable, the story, the myth before they understand what this is.

At the time some people were confused as to whether it was a tribute or a musical or some cartoony thing. Yet the story is very much a child-centred concept set in a world of darkness ... very much like today where people are oppressed.

In the story somewhere is out there with the little hero looking for daylight, the sunshine. It’s a great little story, so I am working on that. The animation project, yes it’s the same people behind the (Beatles inspired) Beat Bugs project.

You have talked about feeling a simpatico with John Lennon.

I love them, I was such a fan of the Beatles.

I felt particularly aligned philosophically strongly with Lennon. We even wrote a similar line by chance; I wrote a song in ‘68 which I never released and later heard in his iconic song Imagine in the context of “dream of the world as one.” And “I’m not the only one”.

There was a kind of synchronicity.

There are other songs you have mentioned may have too much synchronicity with your music.

Don’t forget Coldplay.

That song Viva La Vida ... it was said the similarity was with Joe Satriani (2004’s If I Could Fly. The plagiarism case brought by the guitarist was dismissed in 2009).

If you go back even further, you will come to Foreigner Suite in 1973.

On An Other Cup album (2006), you will hear the development of that same melody, which I stole from myself, and turned into a song called Heaven/Where True Love Grows. And that is much closer I think to what ended up on the Coldplay album.

And hey, I love it.

Come on, on my next album again I have borrowed from myself. And also a melody of Beethoven and turned it into a song.

Songwriters are always casting forward and the tour you will be doing here in November is very much about looking back.

I have great fondness for those songs.

And I bring out hidden gems some people may have missed. There’s a thread, a continuity through them to now.

But the continuity was broken when you quit music in 1979 and didn’t return officially until 2005.

I was just getting down to living the songs, that’s all. Walking the talk, they say.

Coming back to writing again was only when I had something to say.

What had become a bit tedious to me in the end was always this insistence on another album, that cycle.

How thankful are you that your children left a guitar hanging around during a family holiday in Dubai? Is it true that was part of the catalyst for you picking up your music career again?

It was a very strategic move on the part of my son Yoriyos to leave the guitar hanging around and now he’s my manager.

He’s a smart lad and he keeps surprising me, his perception of the world is sharp.

The children love my music. My grandkids, come on. My eldest grandson loves I’ve Got a Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old, he thinks it’s about him. It is; I just didn’t know when I wrote it.

Looking at how it all started for you, growing up in Soho in London with the famed 100 Club down the road and everywhere, do you think you were destined to be a singer and songwriter?

The role I was given early on was a bit of a peacemaker because my mum and dad spilt very early and I was there always trying to hold them all together, it was a big job.

That’s always been my thing, to want to bring sides together.

During your US tour, you let the songs do the talking rather than speak directly about politics or religion from the stage.

No, no, no, that’s not what people come to see me for, they come to hear me for the music.

It was home for me because I brought my attic with me and put it on the walls and the shoes and the trunks that came with me.

Music quite frankly can, does, bring people together, it’s as simple as that. Concerts bring people together, football matches divide them in half and politics just fractures whatever remains.

Forget the rest, go to a gig.

Peace Train still brings audiences to their feet, united in song, more than four decades after it first hit the charts.

The message is still absolutely perfect, the symbol of the movement of humanity, you want everyone to get on that train to get to where happiness resides, for all of us.

It still resounds and it is a great message for what I hope to represent throughout my life.

Are there songs which, since your conversion to Islam, you may feel qualms about singing?

The Boy With the Moon and Stars On His Head is a paradoxical song.

For a start, I’m that kid!

But at the same time it talks about a flirtation before marriage and that’s not really on for a Muslim, is it?

I don’t have so much of a problem (singing) it now because it’s symbolism and the symbolism of that song is nothing other than love.

And love can overcome anything, everything in fact, if it’s pure or not lustful or anything like that. The last words of that song “I’ll tell you everything I’ve learned and love is all ... he said.”

[adelaidenow.com.au, 12. April 2017]

Yusuf / Cat Stevens Announces New Album: The Laughing Apple

Yusuf / Cat Stevens –

The Laughing Apple

Cat-O-Log Records –

15 September 2017

Yusuf/Cat Stevens, one of the most influential singer-songwriters of all time, will release his highly anticipated new album, The Laughing Apple, on September 15 under his Cat-O-Log Records logo exclusively through Decca Records,the same label that launched his career 50 years ago.

Hear the new song ‘See What Love Did to Me’:

The Laughing Apple follows the common ‘60s template of combining newly-written songs with a number of covers – except that all the covers are from Yusuf’s 1967 catalogue. The Laughing Apple celebrates some of his earliest material, presenting the songs as he has always wished they had been recorded.

“There are some I always wanted to hear differently,” he explains. “Many of my earlier recordings were overcooked with big band arrangements. They crowded the song out a lot of times.”

Yusuf produced The Laughing Apple with Paul Samwell-Smith, the original producer behind Yusuf’s landmark recordings, including 1970’s Tea for the Tillerman, which contained the classics ‘Wild World’ and ‘Father and Son’. That multi-platinum album became a benchmark of the singer-songwriter movement, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has named it one of the definitive albums of all time.

The Laughing Apple takes listeners to that little garden where the Tillerman sat under the tree, with a charming new illustration by Yusuf. That picture harks back to Tillerman’s younger days when he worked as an apple-picker. Yusuf also has illustrated each of the 11 songs on The Laughing Apple in his naive style, resembling a storybook — for those whose hearts have never really grown old.

When all things were tall,

And our friends were small,

And the world was new.

Those words of Cat Stevens’ Silent Sunlight now seem to reflect most accurately the sentiments of The Laughing Apple. “As you grow older, the sweetness of youth, as Wordsworth expressed in his poem ‘Splendour in the Grass’, get stronger,” says Yusuf. “Looking back and emotionally drawing on the themes of childhood possibilities and disappointments is what exemplifies this album, for me.”

The new album also marks the return of Yusuf’s longtime musical foil, Alun Davies. Davies, whose graceful acoustic guitar is an essential component of Yusuf’s classic sound, first appeared on 1970’s Mona Bone Jakon and recorded and performed with Yusuf throughout the ‘70s. The Laughing Apple‘s newest songs — ‘See What Love Did to Me’, ‘Olive Hill’ and ‘Don’t Blame Them’ — possess the reflective insight of a spiritual seeker and the melodic charm that made Yusuf beloved by millions during the ‘60s and ‘70s and still speak to a younger, wide-eyed generation.

‘Mighty Peace’ is the first inspired song Yusuf wrote while still beating the folk-club path in London during the early ‘60s. The song laid fallow for more than 50 years, and, with a newly added verse, finally has made it onto an album. ‘Mary and the Little Lamb’ reflects a similar story: it is an unreleased song that existed only on an old demo, and it also has a new verse. ‘Grandsons’ updates ‘I’ve Got a Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old’, which now has hung around long enough to fulfill its biographical destiny. (Yusuf is the beloved grandfather of eight little grandkids.) The original version appeared for the first time on the 2000 edition of The Very Best of Cat Stevens.

Other highlights of The Laughing Apple include new versions of ‘Blackness of the Night’, ‘Northern Wind (Death of Billy the Kid)’, ‘I’m So Sleepy’ and the title track, four songs that appeared in their original incarnations on New Masters, a 1967 album largely unknown in the US.

The album also contains ‘You Can Do (Whatever)’, a song originally intended for the film ‘Harold and Maude’ that remained unfinished until now.

2017 is a milestone marking 50 years of Yusuf / Cat Stevens’ amazing musical history. In 1967, Decca released his debut album, Matthew and Son, on its Deram Records subsidiary.

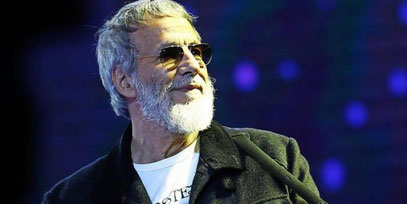

Yusuf returned to the stage at London’s Shaftesbury Theatre, right across from his father’s cafe, on November 20, 2016, with a reflective and deeply emotional delving into his ‘Attic’ of songs, anecdotes and memories. The unforgettable ‘A Cat’s Attic’ show and subsequent tour included his musical classics and global hits like ‘Wild World’, ‘Moonshadow’, ‘Peace Train’, ‘Morning Has Broken’ and ‘Oh Very Young’, which made him a radio staple during the ‘70s. The music of Yusuf / Cat Stevens will be the subject of a PBS Soundstage special in September.

Yusuf’s music has established him as a timeless voice for all generations. His songs are used regularly in films and television shows, with “’Father and Son’ playing during a crucial scene in the blockbuster movie Guardians of the Galaxy 2.

A recipient of The World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates’ Man of Peace award and the World Social Award, Yusuf continues to support charities such as UNICEF, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Tree Aid through The Yusuf Islam Foundation in the UK.

Full tracklisting of The Laughing Apple below:

Blackness of the Night

See What Love Did to Me

The Laughing Apple

Olive Hill

Grandsons

Mighty Peace

Mary and the Little Lamb

You Can Do (Whatever)

Northern Wind (Death of Billy the Kid)

Don’t Blame Them

I’m So Sleepy

[folkradio.co.uk, 21. Juli 2017]

Hear Yusuf / Cat Stevens' Joyous New Song 'See What Love Did to Me'

Track will appear on 'The Laughing Apple,' veteran songwriter's upcoming LP of new and reworked songs

Yusuf / Cat Stevens will release a new album in the fall, his fourth since returning to the folk-pop style of his classic Sixties and Seventies work. The Laughing Apple bridges the artist's present and past, combining newly written songs with covers of tracks from his early repertoire. [...]

The song offers a charming update on the breezy, singalong-friendly sound that Yusuf / Cat Stevens helped to pioneer on classic albums such as Tea for the Tillerman. Over a simple acoustic-guitar-driven arrangement, he praises love's transformative powers, comparing it to forces of nature. "Just like the wind, my heart's rushing fast/A piece of dust too high to catch," he sings. The song's lyric video features animations of Yusuf / Cat Stevens' own drawings, made especially for the album. The artist himself turns up for a cameo near the end of the clip, as the song takes a religious turn: "And now I see what God did for me."

"'See What Love Did to Me' is a a song which extolls the virtue of Love and its destructive properties," Yusuf / Cat Stevens tells Rolling Stone in a statement. "Based on a poem written by Yunus Emre, a Thirteenth Century Turkish poet. I fell upon the guitar riff back in 2006, while recording An Other Cup. It took eight years to find the right words and sentiments to marry with the joyous tune. It has musical ripples of Africa as well as India flowing through."

"Like a blindfolded bee, guided only by his heart to the bosom of the flower, Love is the greatest Divine instinct that gives us wings to fly to the supreme heights of our humanity," he explains, alluding to the song's repeated line "Like a blindfolded bumblebee." "It takes us to a garden where our minds can surrender reason in exchange for the nectar of Love. Worship is in essence a state total devotion to whoever we adore the most and expressing our yearning for closeness and proximity to our Beloved and where we forever want to be."

The Laughing Apple celebrates the 50th anniversary of the artist's 1967 debut, Matthew and Son, and will come out on Yusuf / Cat Stevens' Cat-O-Log Records imprint, via Decca, the label he worked with back then. It also reunites him with producer Paul Samwell-Smith, who helmed Tea for the Tillerman, Teaser and the Firecat and other releases from his early-Seventies heyday.

Among the old songs that Yusuf / Cat Stevens revived and revamped for The Laughing Apple are "Mighty Peace" and "Mary and the Little Lamb," neither of which ever made it onto an album. Four other songs, including the title track, appeared in their original forms on his 1967 LP New Masters. And "You Can Do (Whatever)" was originally intended for the Harold and Maude soundtrack but was left unfinished at the time. "Many of my earlier recordings were overcooked with big band arrangements," he explains in a press release of his decision to revisit this material. "They crowded the song out a lot of times."

The Laughing Apple will be released on September 15th. Last year, Yusuf / Cat Stevens celebrated the 50th anniversary of his first hit single "I Love My Dog" on the retrospective tour A Cat's Attic. [...]

[rollingstone.com, 20. Juli 2017]

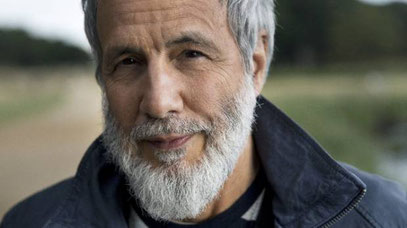

Morning has broken (again) as Cat Stevens returns to the charts after a decade of self reconciliation with an album of gentle lullabies and quiet joy

It has taken a decade for Cat Stevens to fully reconcile himself to being Cat Stevens. When he returned to music in 2006, having abandoned his career after converting to Islam in 1977, he traded as Yusuf. The Cat was firmly back in the bag.

Since then he’s paddled around in the rockpools of his discarded creative identity, but The Laughing Apple signals a full immersion. Reuniting with producer Paul Samwell-Smith and guitarist Alun Davies, both veterans of Stevens’s early Seventies classics, Tea For The Tillerman and Teaser And The Firecat, it’s the first release since Back To Earth in 1978 to be billed as Cat Stevens.

Sound commercial logic? Certainly. But the sense of reclamation extends into the heart of the album, which revisits several of Stevens’s earliest compositions. Four tracks (Blackness Of The Night, The Laughing Apple, Northern Wind, I’m So Sleepy) are reinterpretations of songs from his 1967 album New Masters. Stripped of the over-elaborate production of the originals, they’re presented here in the kind of earthy yet elegant acoustic setting that can’t help but recall Stevens in his prime.

The same mood is evident on Mary And The Little Lamb and You Can Do (Whatever), which date from the same era but were never fully realised, and three new songs. See What Love Did To Me has the direct and devotional beauty of Stevens’s best work, topped off with swooping Arabesque strings. The outstanding Don’t Blame Them finds him once again directing traffic on the bridge across the generational divide, much as he did almost 50 years ago on Father And Son.

Aged 69, his voice still has a guileless quality, a gift for innocence that only occasionally curdles into tweeness. With its gentle lullabies, skipping parables, stern warnings and quiet joy, The Laughing Apple feels like the real deal. A short, sweet return for the most effectual top Cat.

[dailymail.co.uk, 09. Sept. 2017]

Yusuf klingt wieder wie Cat Stevens

Vom gefeierten Popstar zum zurückgezogenen Muslim -

und retour?

Erst jetzt, 50 Jahre nach dem Debüt,

scheint Cat Stevens alias Yusuf

seine zwei Welten endgültig zu vereinen.

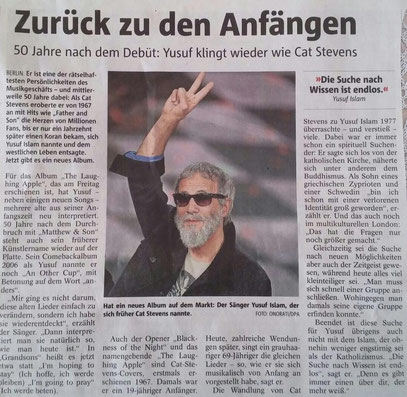

Er ist eine der enigmatischsten Persönlichkeiten des Musikgeschäfts - und mittlerweile 50 Jahre dabei: Als Cat Stevens eroberte er von 1967 an mit Hits wie "Father and Son" die Herzen von Millionen Fans, bis er nur ein Jahrzehnt später einen Koran bekam, sich Yusuf Islam nannte und dem westlichen Leben komplett entsagte.

Zur Gitarre ist der in Dubai lebende Engländer seither längst zurückgekehrt, zunächst mit rein religiösen Inhalten, 2006 dann auch wieder mit Popsongs. Erst das Album "The Laughing Apple" aber, das am Freitag erscheint, scheint ihn vollends mit seiner Vita zu versöhnen.

Für das Album hat Yusuf - neben einigen neuen Songs - mehrere alte aus seiner Anfangszeit neu interpretiert. 50 Jahre nach dem Durchbruch mit "Matthew & Son" steht auch sein früherer Künstlername wieder auf der Platte. Sein Comebackalbum 2006 als Yusuf nannte er noch "An Other Cup", mit Betonung auf dem Wort "anders".

"Mir ging es nicht darum, diese alten Lieder einfach zu verändern, sondern ich habe sie wiederentdeckt", erzählt der Sänger im Interview in Berlin. "Dann interpretiert man sie natürlich so, wie man heute ist." In "Grandsons" heißt es jetzt etwa statt "I'm hoping to stay" (Ich hoffe, ich werde bleiben) "I'm going to pray" (Ich werde beten).

Auch der Opener "Blackness of the Night" und das namengebende "The Laughing Apple" sind Cat-Stevens-Covers, erstmals erschienen 1967. Damals war er ein 19-jähriger Anfänger. Heute, zahlreiche Wendungen später, singt ein grauhaariger 69-Jähriger die gleichen Lieder - so, wie er sie sich musikalisch von Anfang an vorgestellt habe, sagt er.

Wie klingt dieser neue, alte Cat Stevens? Etwas langsamer, definitiv auch ausgeruhter, die Instrumentierung ist reduzierter, weniger Blech. Yusufs Stimme ist gealtert, tiefer - aber sie behält ihren unverwechselbaren Klang. Seine besten Lieder singt Yusuf nicht, er fühlt sie so intensiv, dass andere sie hören können. Er ist, in seinen eigenen Worten, ein "Liebhaber von Melodien".

So deutlich wie nie knüpft Yusuf damit an seine Jahre als Singer-Songwriter an: Die Single "See what love did to me" etwa ist eine beschwingte Folkpop-Nummer im Stil der frühen 1970er - anders als noch die Blues-Songs des Vorgängeralbums "Tell 'Em I'm Gone". Sogar das Titelbild von "Laughing Apple", das Yusuf mit einem "kindischen, naiven Ansatz" selbst gestaltet hat, ist visuell eine Hommage an "Tea for the Tillerman", das der "Rolling Stone" einst als eines der besten Alben der Geschichte kürte. Jedem Song auf "The Laughing Apple" hat der Sänger eine eigene Illustration verpasst.

Die Wandlung von Cat Stevens zu Yusuf Islam 1977 überraschte - und verstieß - viele. Dabei war er immer schon ein spirituell Suchender: Er sagte sich los von der katholischen Kirche, näherte sich unter anderem dem Buddhismus. Als Sohn eines griechischen Zyprioten und einer Schwedin "bin ich schon mit einer verlorenen Identität groß geworden", erzählt er. Und das auch noch im multikulturellen London: "Das hat die Fragen nur noch größer gemacht."

Gleichzeitig sei die Suche nach neuen Möglichkeiten aber auch der Zeitgeist gewesen, während heute alles viel kleinteiliger sei. "Man muss sich schnell einer Gruppe anschließen. Wohingegen man damals seine eigene Gruppe erfinden konnte."

Beendet ist diese Suche ist für Yusuf übrigens auch nicht mit dem Islam, der ohnehin weniger engstirnig sei als der Katholizismus. "Die Suche nach Wissen ist endlos", sagt er. "Denn es gibt immer einen über dir, der mehr weiß." Friedvoller aber als der Sänger, der sich einst rastlos nach Antworten sehnte - ja, das sei er heute schon.

Auf die Frage, ob er denn - ähnlich wie bei seinen alten Songs - auch in seinem Leben als Popstar im Nachhinein etwas ändern würde, überlegt der 69-Jährige nur kurz. "Nicht wirklich", sagt er dann. "Denn es hat Spaß gemacht."

Schon lange vor dem von US-Präsident Donald Trump geplanten Einreiseverbot für Muslime hatte Islam wegen seines Namens Probleme in den USA - 2004 wurde ihm die Einreise verweigert. Seither war der Popsänger, mehrfach wieder in den USA, allerdings noch nicht, seit Trump regiert, wie er sagte. Das werde sich bald ändern, fügte er lachend an: "Auf geht's, wir sind bald auf dem Weg nach New York."

Die Kandidatur Trumps habe er anfangs nicht ernst genommen. "Ich dachte, das ist sowas wie ein Streich ... Aber er hat gewonnen ... Das hatte ich nicht erwartet. Ich glaube, er auch nicht", sagte Islam. "Das zeigt wirklich die Mängel der Demokratie, nicht? Wie die Dinge schiefgehen können, wenn die gewaltige Aufmerksamkeitsmaschinerie im Wahlkampf die Wahrnehmung täuschen kann."

[kleinezeitung.at, 14. Sept. 2017]

"Ich liebe die Beatles. Sorry!"

Der Mann hat extreme Wandlungen durchgemacht:

Vom Weltstar Cat Stevens wurde er 1977 zu Yusuf Islam.

Jetzt bringt der 69-Jährige ein neues Album auf den Markt, das sehr sanft daherkommt. Das habe vielleicht auch mit seinen Enkeln zu tun,

vermutet der Brite.

Ihr neues Album klingt sanft, ruhig, friedvoll, fast schon naiv. Wie empfinden Sie selbst die Atmosphäre, die die Songs kreieren?

Es ist kindlich, es ist sehr ursprünglich. So, wie es ist, wenn man das erste Mal im Leben Farben sieht, das erste Mal neues Essen probiert. Es ist als wäre man wieder ein Kind, also als würde man dem ersten Abschnitt seines Lebens noch mal einen Besuch abstatten. So ist das bei den Songs, und auch bei meiner Kunst, meinen Zeichnungen. Die sind auch im Album, für jeden Song gibt es eine Illustration. Und das Cover ist der "Lachende Apfel".

Also ist das Album so etwas wie die kindliche Seite in Ihnen?

Ja, das kommt wahrscheinlich daher, dass ich jetzt acht Enkelkinder habe, und ich komme natürlich gar nicht drum herum, mit denen zu spielen (lacht). Der Älteste ist zwölf, mein jüngster Enkel ist ein gutes Jahr alt. Und das bringt die kindliche Seite wieder zum Vorschein. Und auch, dass ich mit Paul Samwell-Smith, der mein Produzent bei "Tea for the Tillerman“ (viertes Album vom Cat Stevens, erschienen 1970) war, wieder ins Studio gegangen bin, und auch mit Alun Davies, der damals mein Gitarrist war. Dieses Team ist auf dem Album wiedervereint, und dadurch ist es sehr gemütlich, sehr leicht, sehr entspannt geworden, quasi mühelos. Wie eine Brise, als wir es aufgenommen haben.

Warum haben Sie eigentlich alte Songs und neue Songs auf dem Album gemischt?

(lacht) Es nicht so, dass ich keine neuen Songs habe. Ich habe eine Menge neuer Songs. Es war diese Umgebung, wieder mit Paul und Alan zusammen zu sein. Ich habe ein paar von diesen Songs gespielt, ich habe sie geprobt und dabei gemerkt, dass diese neue Art, sie zu spielen, viel persönlicher ist, viel organischer. Nicht so, wie sie 1967 aufgenommen wurden, damals waren sie sehr orchestral. Also es war eine Rückkehr zu der Reinheit, die die Songs ursprünglich hatten. „Mighty peace“ zum Beispiel ist mein allererster Song als Songwriter. Bis jetzt hat der Song nie das Tageslicht gesehen. Ich hatte sogar den Text vergessen, aber ein alter Freund hat mich daran erinnert, er kannte den Text noch. Ich habe noch eine Strophe dazu getextet, und den Song mit ins Album genommen. Ich finde, er ist sehr wichtig, weil er den Anfang von allem zeigt.

Also ist das Album so etwas wie ein Zusammenfügen von Vergangenheit und Gegenwart?

Ja, aber nicht bewusst, nicht mit Absicht. Sondern dadurch, wie es sich angefühlt hat. Wenn man älter wird, beginnt man zurückzuschauen. Und einige dieser Bilder, dieser Andenken, dieser Erinnerungen, werden plötzlich lebendiger (zeigt auf das rote rbb-Mikophon, lacht und sagt: Übrigens, das sieht aus wie ein roter Apfel – ein lachender roter Apfel!).

Warum haben Sie das Album eigentlich "The Laughing Apple" genannt?

Das ist einfach die beste Zeichnung, deshalb hab ich sie auf das Cover genommen (lacht wieder)! Und außerdem ähnelt es natürlich dem Garten auf dem Cover von "Tea for the Tillerman" - also jetzt, das ist der "Tillerman", als er ein kleiner Junge war. Das war sein erster Job – Äpfel pflücken.

Wären Sie eigentlich gerne noch mal jung?

Das Problem am Jungsein ist, Sie haben die ganze Erfahrung nicht, um zu erkennen, dass vieles an diesem "brillanten Ding, das sich Jugend nennt" (lacht), einfach Zeitverschwendung sein könnte. Man verschwendet einfach viel, sogar seine eigene Gesundheit. Ich meine, ich war ganz sicher nicht besonders nett zu meinem eigenen Körper als ich jung war. Man macht lächerliche Dinge, ob es nun Drogen sind oder irgendetwas anderes. Also: Wenn ich noch mal jung wäre… – Nein, es gibt kein "wenn". Ein Sprichwort sagt: "Es gibt kein "wenn", es gibt nur "was war", "was ist" und "was wird sein"..

Mit welchem Blick schauen Sie zurück in Ihre Vergangenheit? Mit dem Album "The Laughing Apple" feiern Sie den 50. Geburtstag Ihres ersten Albums. Das neue Album klingt besonnen, heiter, kein bisschen bitter.

Wenn Sie ein Album zusammenfügen, wissen Sie manchmal nicht unbedingt, was nachher herauskommt. Man hat eine Menge Songs, und plötzlich fangen die Dinge an, sich zu entwickeln. Eine Art Genre taucht plötzlich auf, wie aus dem Nichts, und bestimmt, was für ein Album das wird. Und so hat es auch dieses Mal funktioniert. Es ist ein optimistisches Album, aber es gibt auch einen Song, "Don’t blame them", der richtet sich gegen Vorurteile. Das ist kein schroffer, harter Song, er zielt nicht auf Konfrontation ab - ich will damit sagen, dass wir ein bisschen tiefer als nur bis auf die Oberfläche gucken sollten. Wir sollten hinter das schauen, was die Überschriften uns manchmal sagen. Jeder hat eine eigene Beziehung mit irgendjemandem, und so sollten wir auch Menschen beurteilen: Mehr nach dem, was wir wissen, und nicht nach dem, was wir hören oder was andere Leute uns sagen, wie wir etwas wahrnehmen sollen.

Geht es in dem Song "Don’t blame them" auch darum, Verantwortung für sich selbst zu übernehmen?

Ja, absolut. Das ist genau der Punkt. Die Menschen geben der Welt die Schuld, der Zeit, dem Wetter. Immer, wenn wir nach einem Schuldigen suchen, sollten wir erstmal bei uns selbst schauen, denn am Ende sind es wir selbst, die über unsere Wahrnehmung bestimmen. Und damit bestimmen wir auch darüber, ob etwas im Dunkeln glüht – oder ob es dunkel wird.

Damit hat der Song eine klare Botschaft…

Ja, das stimmt. Und auch der erste Song, "Blackness in the Night", hat eine Botschaft. Das war mein erster "Protest-Song" über die Welt, wenn man so will. Er handelt vom Krieg, von Waisenkindern, und der Song ist leider auch heute sehr aktuell und relevant.

Gerade haben sich die Terroranschläge vom 11. September zum 16. Mal gejährt. Was meinen Sie – ist die Welt seitdem besser oder schlechter geworden?