Stephen Giorgio and Alun Davies sat in straight-backed chairs facing 2300 non believers. From the Fillmore East balcony, Cat Stevens and partner looked hopelessly tiny. Just two seated figures holding guitars; no banks of amps, no massed drums, no sparkle suits.

From the audience came a continuous buzz, as if each member was surprised by the puniness of the foe. Still, the crowd would have to amuse itself by toying with these already overwhelmed figures - perhaps even shame them off the stage.

‘‘Hello.’’

What was that? The dark-haired one had greeted the crowd as if he didn’t realize the danger. He began to play his funny little songs while the audience talked over him. But he didn’t appear to be bothered by the crowd’s lack of commitment - in fact, he seemed to hardly notice.

For the people who were waiting ever so patiently for Traffic to appear, this little upstart had a very annoying habit: he spoke between songs as if he were in someone’s apartment for the first time - polite, friendly, warm. This kind of intimacy was practically unheard of at the Fillmore, with its reputation for toughness. The kid must be awfully naive. .

.

Forty minutes later, this unknown who called himself Cat Stevens had the audience on its feet, not in derision but in happy surprise. No one there that night had ever heard of "Wild World," or "Hard-Headed Woman," or "Father and Son." They’d had nothing to go on except this kid’s straightforward charm. Along the way, the crowds had also learned that Cat Stevens could write songs - and sing them, too - like nobody else. The word spread - gradually, it’s true, but steadily - about this innocent who had shown up Traffic on its home ground.

The next week, Steven Giorgio’s appearance at the tiny Gaslight attracted some of the same people who’d been soothed into submission at the Fillmore. At closer quarters, it was immediately evident that the kid had a singular and irresistable charm to match his talent. In his naivete, he ribboned his songs with unembarrassed, "oohs" and "la-la-la's," and he seemed to enjoy mouthing the syllables. And be used his voice as a little boy would greet his dog. He eagerly bounced from the top to the bottom of its range and back again, glorying in the texture and the feel of it. The unallayed joy he gave himself through his own performance was quickly and evenly distributed among the people who listened.

On top of everything else, Cat Stevens showed himself at close range to be the owner of a finely structured, beautifully open face. A slightly uneven nose kept the face from becoming too proud of itself - kept it from any tendency to take a condescending attitude. The gold of Greek ancestors had been willed to him and he wore it proudly on his skin. His natural Adriatic intensity was balanced by an easy, gentle spirit.Upon seeing him up close, we had an inkling that it was just a matter of time. We were right.

The next morning, AIun Davies confessed he was worried that people would think he and Steve sounded too much like Simon and Garfunkel (a notion that I'm sure had occurred to no one who’d seen them). Paul Simon’s mid-60’s stay in England, and the solo album that resulted from the stay, had indeed been an inspiration to Steve and to many other aspiring English folkies and songwriters. The Paul Simon Songbook (never released in the US) is still among Steve’s favorite albums. The Simon influence is there, in fully assimilated form, but only in some of the melodies. Cat’s songs are much brighter and freer than Simon’s. Steve’s not haunted by the same ghosts. He’s already exorcised them.

A long bout with tuberculosis put an end to the barely begun career of adolescent Cat Stevens. Before he fell ill, Steve had completed two albums for Deram. Both were filled with clever little songs but burdened with insensitive and heavy-handed arrangements. Another shortcoming: At the time, Steve had no idea what his voice could do. He failed, as a singer, to really take command of his songs - to seize each song by the hair and ram it across, as he does so well now.

His recuperative period was also a time of continuous self-analysis. Steve's bad fortune had its benefits: It’s not often that an individual has the opportunity to take stock of himself just as he's about to embark on his chosen vocation. Young men are too busy doing to reflect - that is, if they can sense success within their reach. The knack of reflection is normally acquired only after this prolonged exertion of youth.

Cat Stevens might have become another mediocre middle-of-the-road pop singer if TB hadn’t stopped him; the photo on the cover of his New Masters LP, on Deram, makes him out to be an eager young Anthony Newley. From "Matthew and Son" to "Why Can’t I Fall In Love" isn't really so great a distance. But good fortune prevailed, discussed as tragedy.

It was apparent to me the morning I met him that this guy was really happy. We see genuinely happy people so rarely these days that the real thing stands out. He was still a nobody at that point last autumn, but that didn’t matter. Steve was flushed with the certainty that he was doing exactly what he wanted to do. It was a bonus that people seemed to like what he did.

During his convalescence, Steve had begun writing songs again. These songs were different than those he’d written before his illness - they had a cathartic effect on him. He faced his old adversaries - fear of rejection, self-doubts - in his new songs, and he found he could beat them. With his new confidence came his new voice - rangy and virile, but capable of an equally dramatic gentleness - and the rest fell into place.

Mona Bone Jakon, the name of Steve’s initial effort in his "second" career, is said to refer to one’s inability to get an erection:

"I’d already done that drawing of the garbage can with the drop coming out of the top. When I thought of it in relation to the album title, it sort of made sense, so I made it the album cover."

When he talks about his life, feelings of inadequacy pop up in his words:

"The first song l ever wrote was called something like ‘Darling Mary,’ or 'Darling Nell."

What inspired you?

"I think it was bein’ rejected from her door - Oh, no it wasn’t." he laughed, all but triumphantly. "It was terrible. It was my friend, you see, and I used to go to see my friend. He had a very big family and lots of sisters. I used to go there mainly to see my friend and then suddenly I became aware of one of his sisters. So while he was downstairs, I’d be upstairs with his sister, and he never got on to it; he never found out anything about. it. So it was that kind of scene and I was struggling to express it. I was very weird then."

After spending those months on the road to find out, Cat seems to have resolved those kinds of conflicts. The biggest question facing him that morning last autumn concerned the release of a Cat Stevens single: Should he let them do it? If so, what?

"I think it’s a good idea not to release a single just yet: Maybe they’ll want one from the LP in about two months’ time ...... for when I come over next."

It turned out that Steve had an impeccable sense of timing. At the time, everybody was too busy with Elton John and James Taylor to pay another new one any attention (at the time, I couldn’t even talk my good friend the editor into letting me review Tea For The Tillerman, Cat’s then brand new album). Two months later, as the populace wearied of all that hyper-aggressive promotion, what should quietly float into the choked atmosphere but ".. . ooh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world, and it’s hard to get by just upon a smile," words and melody so beautifully unprepossessing that hardly anyone could resist it.

"Wild World" gave Tea for the Tillerman enough kick to get it played on FM radio and the exquisite album that Island Records boss Chris Blackwell had unequivocably called "the best album we’ve ever released" (and that meant he felt it was better than Mr Fantasy, among others) began to enchant listeners on a mass scale.

That was the icing on Steve’s cake. The second time around, he played to packed-full houses, to audiences that were as excited before he came on as they’d been after the encore during his first tour. But that didn’t change anything basic. On stage, he was still refreshingly innocent and direct. Oh, he was delighted by the warm response, but then he’d been equally delighted at winning over initially hostile audiences a few months before. (at the end of that now-legendary Fillmore set, he stood and bowed to the waist, then embraced Alun warmly - that lovely show of humility had gotten to even the diehard cynics who’d resisted his charm and skill up to that point).

And little things still delight him as well:

"It’s kind of funny when somebody suddenly says, 'Wow you sound like an old guy!’ " he laughs. "I can’t imagine my voice as being quite like - well, I did imagine it being quite medium range, you know. A normal voice, but a bit harder. But to some people it sounds very old."

A small thing, but revealing, nonetheless: he listens to people - that’s his nature - and now, because of his rapid commercial success, he's getting a volley of feedback. That worries him a bit:

"The thing that went wrong with the Beatles is they actually started writing for the people who were reading into their songs. At first, they let it happen from inspiration, and perhaps they wrote something that they didn’t know what it meant. And then finally they started reading about what it all actually meant, and then they became more obvious."

When you set out to write something, do you have a story you want to tell? I mean, do you have something very specific or does it come from words that you just kind of pull out of the air?

"I start out with something specific, and it always ends up that I completely change my idea. And I write something that is absolutely - like just inspiration. I start out being calculated, and from that point, I fall off. And like, uh, I start from there."

And then you have to go back and change the beginning.

"No; I never finish that one. The first one I start I never finish. It's always something new - I write another riff or something and then start over. That’s how you do it: You get on to a line and then fall off. And that’s where you are. And the moment you know that you’re there, that’s when it stops. That’s where everything stops. Intellectually, I can’t write."

It’s fitting that creative calculation is outside his grasp, because everything about Cat Stevens the performer is without affect. Naturalness is at the core of his effectiveness as a writer and as a performer. In the strict sense of the word, Steve doesn’t perform at all - he just is.

That’s all there is to him - but it’s plenty.

[Rock Magazine, 24.05.1971]

Cat Stevens, Superstar?

"I hope I never get to that point"

Cat Stevensis back with us, has a new album, some thoughts on leading the happy life, and several succinct words about coming a hype away from death.

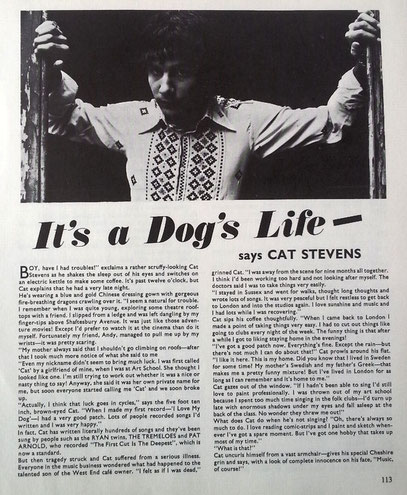

He is either stoutly defended as one of the five greatest composers of our time or vaguely remembered as an odd name in the English music scene that flashed briefly in front of our eyes and then vanished.

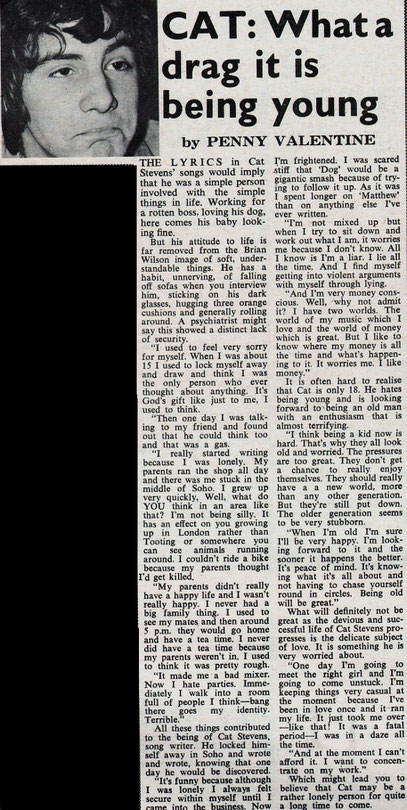

Five years ago straight out of art school, he rose to brilliant stardom with "I Love My Dog," "Matthew and Son," "I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun," "First Cut Is The Deepest."

At seventeen he was a full-fledged pop idol.

People grabbed at him at parties, pumped his hand, and steered him into corners to tell him they loved his work so much. He had rave reviews from every publication in England that could get someone into see him. He was on the cover of a tremendous number of music in papers. The photographers snapped away, click-click-click.

And then there was such a social scene, so many parties and celebrities adopting him and places to see. Managers, musicians, fans and critics built up his ego till it got to the point where he was swell-headed. When he speaks of his past, today, all his expression coming from his voice, which plays on patterns of speaking that simply don’t exist here - he makes you wish you’d been there, to see the outrageousness of the Superstar scene: the flags, the banners, the horns, the blaring ego. Talking in his dressing room in Buffalo, during a tour with Traffic, he doesn’t remind you of the fiery star of the mid-sixties.

As a Cancer he has soft and gentle beauty in the features of his face, very much like an angel in a Renaissance painting, the look of original innocence joined with a genuinely shy manner and soft, youthful voice makes him outwardly appear younger than his 22 years.

His expression is darkest when he speaks of those early recording sessions in which the producer’s rules and goals conflicted with his own. The multitude of studio musicians were also apparently less than impressed with being a Superstar and consequently gave him all manner of overproduction as well as a hand, the result being you had to wade through so much plastic fluff to get to Cat Stevens.

"We had a twenty piece band," recalls Cat, disgustedly. "Everytime we were in the studio none of them were really interested in what we were doing. Nothing to do with it. They were just getting paid."

What really upset him was the most commercial, the beatiest or the simplest songs were picked by his recording company to be released. His own suggestions were ignored.

At the beginning he thought he could cope with everything. But then events were blurred, blown right out of proportion. The songs were over-arranged right into the ground. In a short time he entered into a long series of disastrous flops. The first record which missed was, ironically, "Bad Night." Physical disaster struck in the form of tuberculosis and he was hospitalized in September 1968 for three months. Then he traveled, made friends (he never had any before) and thought about his past style of life.

"I dropped everything for a time and then suddenly I realized what I wanted to do," he says. "I wanted to do it again only I wanted to do it right. I wanted to do it truthfully. Before it was all messed up. I didn’t have my ideals right. I was completely upside down.

I realized that although I’d spent all that time working and striving, I still knew nobody. I was lonely. I thought ‘what’s the point of living here if you have to live alone?’ I decided then to get myself together as a person. I was an instant public figure but had nothing to myself except what I felt. It’s all right to feel something but it’s nice to know what you feel.’’

Almost a year ago, Island Records released "Mona Bone Jakon," Cat’s first album in two years. It was a wonder summary-with-introspection and so simple. He played piano, organ and guitar; and was backed up by an additional guitar, a bass, flute and percussion. The mesh was ideal, the lyrics, voice and music caught his mood perfectly. Yet, the superb album generated less than its share of praise among pop critics and journals. One cut, "Lady D’Arbanville," reached #4 on the British chart and was a regional hit in Canada.

The recently released "Tea for’ the Tillerman," an extension of the basic idea he investigated in the previous album, is quite possible the best record, the simplest, to appear in the last five years.

Although it deviates little from the track laid down by the earlier album; it is immensely popular in North America (it was big in England before - because of: 1) the tour with Traffic; 2) individual appearances at The Bitter End in New York, and Doug Weston’s Troubadour; and the publicity devoted to it by A&M Records (Island’s North American distributor).

Its success brings the possibility of Cat again being confronted with the tag superstar and its implications. "I hope I never get to that point," he says. "I keep an eye on myself and if that happens, I’ll realize it. Actually, the only thing to do is to split because it’s not for money.

I think it had a lot to do with myself at the time. I wasn’t strong. I was ready for something like that. I see myself so much stronger now.

Things are starting to happen with the records, and I’m going to start getting pressurized again. I think this happened with The Band. Their third album was like that. I’ll never get to that point again.

The two albums were well received in England. It’s given me a lot of freedom to do what I want to do. The people there have always been ready to listen to what I’m doing - even if I do, like in the old days, a bad one."

The song "On The Road To Find Out," from the new record, is the most autobiographical of his material. It directly relates to his experience of finding himself and concludes: "Then I found my head one day when I wasn’t even trying."

"You can’t plan it," he warns, unsmiling. "It just happens and that’s the moment. You’ve got to reach that thing. You think about it: its gone completely. So you have to let your instinct guide you. I wasn’t even trying stint guide you. I wasn’t even trying. That was the moment I was relaxed and-ready to take it."

He has also done a very nice thing for modern-pop music: he has injected into it a sense of duality. He paints his picture-songs with a dab of irony and a dash of awe, and somehow never neglects a delicate balance of pessimism arid optimism.

For example "Father and Son" gives two contrasting views of life: a wise, weary father tells his son that it’s not time to make a change, to relax, take it easy. The son answers that it’s always been the same old story - "From the moment I could talk I was ordered to listen, now there’s away and I know I have to go.’’ "I realized - I lost my ego," says Stevens. "That was the main thing. That’s how I managed to write that song with two people in it. They’re both right. You take a lot of songs and maybe its only one person saying it and they’re saying one thing. And that’s quite definite. But I don’t feel that definite about my ego anymore. I’ve had a very big shock and that’s I feel quite frightened sometimes that I don’t have this confidence a lot of people still have because I don’t think about that.

First of all you do things for yourself. That’s why you start. You love yourself. It would be useless for me to write songs just for me, if I thought I was just writing it and no one would ever hear it. I wouldn’t write it because I’ve already got it in my head. The fun of it is getting it across, to get people in saying they like it. That’s the pay-off!"

He described the struggle it was for him to break through the ego to that forgotten naturalness.

"Finding that centre, that simple thing," he says, "can take a long time. Once you’re there you can go for miles. It’s just finding that spot. It can take someone 50 years. With me I was lucky because I had an illness that helped me to get nearer to where I was originally.

Some people are two different people when they go out and sing and when they write to who they’re friends are and who they mix with and what they say to them as well. The greatest thing to me is to bring those two worlds together. If you actually say something to somebody and they understand what you mean and they hear your record and they understand what you mean and they see you and they understand what you mean - you’re one. That’s where it all works, when you’re home. A lot of people just run around as fractional - bits here, bits there."

He returns to pessimism and optimism to illustrate his present position."I feel both. It’s the same thing. Like "Maybe You’re Right, Maybe You’re Wrong" on the first album, I take both sides. I want to stand in the middle all of the time because that is a guide for me.

It’s no use being happy and every. one else being unhappy because that won’t make it," he cautions, stroking his beard. "There are so many unhappy people that we’ve got to take this point of view in order to come through to their way. Otherwise if you’re completely happy, they won’t be able to see or grab it quite as completely, as if you’re right there with them. Now you say: ‘we can go up’. That’s much easier."

In this case the performer is largely his own producer - he has translated concept Into actuality with remarkable grace. Studio electronics is an extremely structured affair and the artificiality at the core of creation has stunted the artistic growth of a number of musicians. But thanks to the calm surefootedness of Stevens, producer Paul Samwell-Smith, a small number of back - up musicians, the record company, there has been no flaws; Cat Stevens has been delivered to the public fully grown (by current standards) and as still growing (standards change).

"It takes work," he says, smiling.

"Immediately you get a song you want to put in drums. You want to put in boss. You think ‘how am I going to . . .‘ That doesn’t work anymore. At least not for me. I like to be surprised. it has to fit perfectly not lust drums, rhythm. It has to be much more than that - the awareness you get sometimes Into a song. That’s why sometimes I break in to the middle, completely, suddenly. You’re got people. The moment it stops, It begins. It’s like you don’t have to play so loud. In fact the quieter you play the more people will listen."

His songs are written during moments when he isn’t really thinking about doing It. When he’s not hung up in any particular way.

"It could be anywhere" he reveals, "but I save, to be by myself. If I have someone In the room that’s great because you get vibes from the start - the rhythm or something. But to finish it, to get into the intricacies of it; I have to be by myself.

The greatest thing is to sit down and write lyrics. Sometimes I have a tune and I say ‘what is this tune and why did I write this tune and what are my feelings and what emotionally does it mean to me'.When I find out I say ‘right.’ That’s what I’m going to write about.

In the studio you must start again," he adds, after a pause. "You’ve written the song now you have to sing It. You’re got to record it. You have to create It again. Almost have to write it over. It’s never the same as when you first wrote it."

However, he has released two strangely beautiful albums, solid enough to be a collection of 45s. The images are easily real and the music is profoundly comforting; yet there’s the edge of a story that fades without ever revealing oil it has to tell. Perhaps, a third album will complete the tale.

What is important is something is happening with this British composers and people lust ought to know about it.

[Hit Parade 1971]

Cat Stevens' Return: Pop Goes the Poof

Every moment, every song is important to the artist

London — Two children, one black and one white, played on the doorstep of Cat Stevens's terraced house.

"Are you here for the interview?" asked one. "He's in there," pointed the other, as professionally as a tour guide, even though the occasion was a rare one.

Stevens was entertaining a group of reporters on the eve of a tour that would take him to the U.S. for 24 dates, beginning April 22nd in Detroit and ending May 20th in Los Angeles. He would conclude the tour with concerts in Australia and Japan. And he had just released a new album, Buddha and the Chocolate Box, and the initial impression was that Cat was back to his pre-Foreigner ways, with shorter, poppier tunes, sweets but no 18-minute suites.

Stevens eased himself into a crosslegged position on the floor of his living room and explained the title of the new album: He was on a plane to Florida a year ago, he said, and he was carrying a small porcelain Buddha figure and a box of chocolates with him.

"I suddenly realized that was all I had. Whether I died or not, it would just be the Buddha and the chocolate box. I was trying to find the significance in that when I realized that was the significance. That's all that had to be known."

Cat dispensed more philosophical bonbons: "One cannot discount any moment in one's life. There is no moment that is not important. Just like the boy on the back of the album finds enlightenment from a chocolate box [in a cartoon strip conceived and drawn by Stevens]. You can find it from anything. It's like meditation, you can look at a piece of paper and find anything you want in the piece of paper."

Cat's cloudy ways of expression follow him onto the stage. At the Theatre Royal in London in late March, he castigated himself for moving across the stage with "the walk of a poof. I'm just a poof. Well, maybe not. What's the opposite of poof? Heterosexual? Well, then, I guess I'm just a 'heto.' Well, I don't really know."

Shortly after that interlude, Stevens told the house that Foreigner hadn't sold too well, but that didn't mean much, since chart positions weren't important to him. Then he went on to exclaim: "The new one went in at number 16!"

However puffy, Stevens seemed sincere at his home, trying to explain his albums, the ambitious Foreigner and the new one, on which he's reunited with producer Paul Samwell-Smith.

"Paul and I were getting too familiar before Foreigner," said Cat. "Being away got us excited about going into the studio again." Samwell-Smith had teamed with Stevens to produce Tea for the Tillerman and Teaser and the Firecat.

"Foreigner was like going away for a while," said Stevens. "People want to hear from you. I'm not going too far, I never want to be out of reach, I want to be here for anybody who wants to relate to me. So after Foreigner I wanted to say, 'I'm still here, you don't have to worry about it."

The single from Foreigner, "The Hurt," failed to make the British charts and barely reached the Top 20 in America. "I've always been a bad picker of singles," said Cat. He chose the new single, too, he said, "but I got a lot of other people to give reactions because I love it so much." It's called "Oh Very Young."

"I've seen youth lost," Stevens reasoned. "I've watched myself grow, and seen my attitude to children change. One must always change, that's what children do. I find a lot of people take their kids for granted, even people who were in the hippie thing. I haven't broken the line yet. I still enjoy the kids on the street, and there's a school across the back that I'm looking forward to visiting."

Stevens drew puzzled stares from several of the reporters at his house when he began drawing a connection between Buddha and Jesus Christ, who both rate a verse in the song, "Jesus."

"I see no difference in what they were doing," he said. "Jesus died . . . really . . . not violently, but on a cross which became the symbol of Jesus . . . whereas Buddha didn't even die as we know.

They were both saying exactly the same thing, which is why I think of them both."

As if to match the spiritual mood of Cat Stevens, the stage design for the American portion of his tour is all in white. A white nylon band shell was built in Los Angeles. Described by one crew member as "kind of floating, like half a flower," it will serve as background for two grand pianos — white, of course — and an expected company of ten musicians and singers behind Stevens.

It appeared from his London performances, however, that Stevens was not yet comfortable onstage. After a generally uninspired performance, he said goodnight to the opening-night capacity crowd at the Theatre Royal: "Well, that's all for another year." He told the audience they had been "nice, but cool — but then, I was cool, wasn't I?"

[rollingstone.com, 9. Mai 1974]

Cat Stevens steckt voller Komplexe

Drury Lane Theater. London.

“Cat Stevens” strahlt eine riesige Leuchtschrift über dem wuchtigen Portal. Darunter drängt sich eine bunte Menschenmenge. Freaks, Kinder mit ihren Eltern, alte Ladies und junge Mädchen mit glänzenden Augen. Zwischen ihnen wieseln Kartenschwarzhändler herum und machten das Geschäft ihres Lebens. Normale Tickets gibt es seit Wochen keine mehr, der Vorverkauf war innerhalb von drei Stunden beendet. Wer jetzt noch Cat sehen will, muss Phantasiepreise von 80 und mehr Mark zahlen.

20.00 Uhr. Langsam verlöscht das Licht im pompös verplüschten Saal und je dunkler es wird, desto lauter schwillt der Applaus an für Cat Stevens, der zusammen mit seinem Gitarristen Alun Davies die Bühne betritt.

Umständlich packt er die Gitarre, stimmt, sagt „Hello“. Die ersten Akkorde von „Bitterblue“. Sofort jubelt das Publikum wieder, verharrt drei Minuten, dann, mit den letzten Tönen, braust der Beifall wieder

los. Nach fast dreijähriger Pause ist Cat auf die Bühne zurückgekehrt – und schon jetzt wollen ihn die Fans im Saal nie mehr gehen lassen.

Cats Band taucht aus dem Dunkeln auf. Pianist Jean Russel, Drummer Gerry Conway, dazu ein Bassist und ein Percussionmann. Ohne Ankündigung spielt Cat weiter, „Wild World“, die traurige Ballade von der Geliebten, die ihn verlassen hat.

Zwischen und während der Songs rufen die Fans immer wieder ihre Lieblingssongs. Cat geht auf jeden Ruf ein, man sieht, daß er dankbar und froh ist über diese Kommunikation. Auf der Bühne fühlt sich Cat Stevens nicht sehr wohl, man merkt es, er wirkt sehr gehemmt. Seine Bewegungen sind linkisch, und wenn immer er etwas sagen müsste und gerade kein Zwischenruf die Stille unterbricht, stimmt er lieber umständlich die Gitarre, um seine Unsicherheit zu verdecken.

Cat steht auf, wechselt hinüber zum Piano.

Plötzlich merkt er, daß seine Unsicherheit beim Gehen den Zuschauern aufgefallen sein muss. Er greift zum Mikrofon. „Habt ihr gemerkt, dass ich mich eben wie ein Schwuler bewegt habe? Aber ich bin nicht schwul, ich bin heterosexuell.“

Das Publikum lacht, Cat grinst, die für ihn peinliche Situation ist überwunden. Ein paar Griechen rufen etwas in ihrer Heimatsprache. Cat (der eigentlich Steven Dimitrios Georgiou heißt und hellenischer Abstammung ist) antwortet auf Griechisch, fasst sich - den Erschrockenen mimend - an den Mund: „Bloody Greeks, shut up!“

Er schaut schnell in die Runde, sieht in lächelnde Gesichter. Man mag ihn. Und die Frauen im Saal lieben ihn.

Zwei Stunden lang spielt sich Cat – nur unterbrochen von einem kurzen Intermezzo der süßen Sängerin Linda Lewis – durch sein Repertoire. Er bringt „Lady D’Arbanville“ von seinem ersten Album und Songs seiner letzten LP „Buddha and the Chocolate Box“ ebenso wie seine sehr persönlichen Titel „Sad Lisa“ und „Father and Son“.

Dann geht er, so still wie er kam. Der Saal aber tobt.

Später.

Cats Plattenfirma lädt zum Empfang nach dem Konzert. Cat erscheint als letzter. Die Hände in den Hosentaschen, den Kopf leicht vorn übergeneigt, schleicht er durch Massen von Reportern, Fotografen, Musikerkollegen, Fans und Familienangehörigen. Überall wird er sofort angemacht, Frauen umarmen, Mädchen küssen ihn, Journalisten stürmen auf ihn ein. Cat wird rot, versucht Fragen mit einem freundlichen Lächeln zu quittieren. Autogramme gibt er freiwillig, doch Auskunft ist nicht drin.

Auf die Frage eines vorwitzigen Jung-Reporters nach einem Interview antwortet er höflich, doch bestimmt:

„You know, du willst mich benutzen und mit mir Geld verdienen. Aber: I don’t want to be used. Ich will nicht benutzt, ausgenutzt werden!”

Cat Stevens, der Superstar-wenn-er-nur-wollte, der traurige Liebeslieder und Balladen schreibt wie kein anderer, kapselt sich systematisch ab. Er ist einsam und will es sein. Seine Freundinnen verlassen ihn immer wieder – Cat macht Songs daraus. Seine einzig wirkliche Freundin ist die Musik, eine Freundin, die auch in einsamen Stunden bei ihm bleibt.

Seit er 1966 zum ersten Mal in die gnadenlosen Maschinerie des Show-Business geriet, sich an ein Management verkaufte, von der Plattenfirma ausgenutzt und vermarktet wurde, und ihm nur eine lange Krankheit die Chance zum Absprung gab, lässt er sich nicht mehr auf die Spielregeln des Showgeschäftes ein. Cat Stevens will Cat Stevens bleiben, so wie er sich sieht. Auch wenn dies bedeutet, mit all den Komplexen und Problemen, die jeder von uns und Cat, der Sensible, ganz besonders hat, allein fertig werden zu müssen. Auch wenn man Nacht für Nacht von den Massen geliebt und gefeiert wird und mit dem Wissen, dass seine Platten vielen, die ebenfalls einsam sind, ein wenig vergessen schenken...

[POP 1974]

[sounds 1975]

Cat Stevens, in aller Welt erfolgreicher Pop-Musiker, lebt privat sehr zurückgezogen. Das Interview fand im Büro seines Managers statt.

Der Junge, der Cat Stevens unterhalb der Bühne zu Füßen sitzt und dessen Amt es ist, Steve eine andere Gitarre zu reichen, wenn an der Bespielten eine Seite gesprungen ist, singt Wort für Wort die Texte mit. Viermal an diesem Abend in der Münsterlandhalle reicht er ihm das nächste Instrument, etwa wie ein Sekundant dem berühmten Fechter einen neuen Degen reicht, Verehrung im Blick und im Herzen. Die Ovationen von 5000 Fans in Münster wogen über diese kurze, intime Szene hinweg. Steve (der von seinem Manager Cat getauft wurde, aber privat so nicht angesprochen werden will) kennt den jungen Engländer seit langem, und der Junge begleitet ihn auf der ganzen Deutschland- und Europatournee, von Münster nach Barcelona, von Barcelona nach Thessaloniki.

Als Steven Demitri Georgiou, in London 1948 geboren, etwa das Alter seines jugendlichen Verehrers von heute hatte, da wusste auch er einige Popstars, denen er gerne die Instrumente gereicht hätte, Little Richard zum Beispiel. Damals drückte er in London noch die Schulbank, mit guten Noten nur in Zeichnen und Musik. Aber er hielt sich nicht lange damit auf, andere Musiker zu bewundern. Stattdessen produzierte er in London seine erste Single und die hieß ausgerechnet „Back to the good old times“. Er war siebzehn und er sehnte sich nach „den guten, alten Zeiten“.

Vielleicht sehnte er sich wirklich nach den Tagen seiner Kindheit und nach den vielen schönen Damen, die den zarten Knaben mit dem dunklen griechischen Kopf in den abendlichen Straßen von Soho verstohlen übers Haar strichen. Die zärtliche Verehrung ist ihm treu geblieben, die vergebliche Sehnsucht nach Liebe und Erfüllung, die jene Prostituierten schon in den Knaben geweckt haben mochten, auch. Sein Vater ist ein griechischer Restaurantbesitzer, eingewandert einst aus dem armen Zypern, seine Mutter Schwedin. Gewiss ist das Griechische in Steve, das die zärtliche Melancholie in seinen Liedern und Texten bestimmt, die vor allem Frauen bezaubern. Aber es ist auch das Griechische in ihm, das leidenschaftlich Besitzergreifende nämlich, durch das die Nähe einer Frau für ihn zum Problem wird.

„Es ist lange her“, sagt er, „da haben mich die Frauen eifersüchtig gemacht. Ich wurde buchstäblich aufgefressen von meiner Eifersucht, bis nichts mehr von mir übrig blieb. Ich musste lange Zeit dagegen ankämpfen. Die einzige Art, sich dagegen zu wehren, ist die, dass man Frauen nicht zu eng an sich bindet. Heute kann ich das“.

Ich verstehe das nicht. Ich sitze im Londoner Büro seines Managers Berry Krost gegenüber und denke, daß er auch mich verzaubert, mich, einen Mann. Seine Augen sind dunkelbraun und klar, und irgendwo zwischen dem schwarzen Haar und dem schwarzen Bart dieses mächtigen Millionärs in T-Shirt und Jeans mischen sich Wehmut, Charme und Schalk. Das konnte Andy Warhols „Flesh“–Darstellerin Patti D’Arbanville, Steves unerfüllte einstige Liebe, nicht fesseln?

Sie verließ ihn und betrog in mit Mick Jagger. „Du verlierst ein Mädchen“, sagt Steve, „aber das macht nichts. Irgendetwas wird geschehen“. Auch damals geschah etwas:

Cat Stevens schrieb den Song „Lady D’Arbanville“, und der wurde ein Hit.

Er schrieb immer zuerst die Melodie („danach bin ich sehr glücklich“), und dann singt er das Lied. Er spielt Piano, Gitarre, Mandoline, Flöte, Orgel, Schlagzeug, Bassgeige und Synthesizer, und diese Woche lernt er Saxophon. Er hat Filmmusik geschrieben, zum Beispiel für „Harold and Maude“. Aber sein Begabungsreichtum ist noch immer unerschöpft, sein Verlangen, sich auszudrücken, noch immer ungesättigt. Der ehemalige Kunststudent entwirft und zeichnet seine Plattencovers selbst. Er hat 50 Entwürfe für einen Zeichentrick fertig, den er bald in der Tschechoslowakei produzieren will. Sein Titel: „Numbers“.

Auch Cat Stevens hat, wie viele seiner Kollegen, auf seinen Introspektionen, seiner „Schau nach innen“, seiner „Suche nach Gott“, den Rat eines Gurus angenommen. Im Augenblick beschäftigt ihn die Kabbala, die Mystik der Zahlen, deshalb der Filmtitel, deshalb der gleichlautende Titel seiner letzten LP. „Es ist ein mystischer Film“, sagt er, „ein pythagoreisches Märchen.“

Und dann sagt er etwas, was ich hinnehme, ohne es zu verstehen: „Als die Araber die Null endeckten, wurden viele Dinge klar.“

Das sind die Resultate eines mehrmonatigen Aufenthalts in Brasilien. Auf einem Hügel bei Rio de Janeiro, nahe der berühmten Christus-Statue, hat er sich eine große Wohnung eingerichtet. Warum dort? Steve: “Brasilien ist ein junges Land, jünger als der alte Kontinent.“

Cat Stevens geht seine eigenen Wege. Den Rummel der Popmusik-Zentren, etwa von Los Angeles, macht er nicht mit, er hasst Los Angeles. Den Zwängen des Popmusik-Marktes und dem bestimmenden Zugriff der Plattenindustrie hat er sich immer entzogen. Er ist nach Äthiopien gefahren, als da der Hunger war, weil er den Hunger sehen wollte, und er hat viel Geld zur Bekämpfung des Hungers gespendet. Dann hat er sich die Haare und den Bart geschoren und lange über sich nachgedacht. Derlei tat er schon öfter, und jedes Mal wurde seine Rückkehr von der Musikpresse als seine zweite, seine dritte, seine neue Karriere gefeiert. Denn jedes Mal kam er mit neuen Liedern, die Hits wurden.

Im Augenblick liest er den Koran, der ihm „reiner“ zu sein scheint als die Bibel. Im Augenblick liebt er ein Mädchen, eine junge Österreicherin, die zur Truppe von Andre Heller gehört. Sie lebt in Wien. Cat Stevens liebt sie, ohne sie zu eng an sich zu binden.

[Brigitte, 1976]

In der ersten Reihe

sitzen Keith Richard und Ron Wood von den Rolling Stones, daneben Chris Jagger, der kleine Bruder des berümten Mick. Gemeinsam mit 9000 Fans warten sie in der Münchner Olympiahalle, daß sich der

schwarze Vorhang mit dem aufgestickten Tigerkopf heben möge.

In der Garderobe stimmt Cat Stevens währenddessen ein letztes Mal seine akustische Gitarre und spricht mit seinem Blonden Gitarristen Alun Davis noch einmal die Songs durch. Zwischendurch ißt er:

Spargel und Gemüse. Cat Stevens ist Vegetarier. Fleisch rührt er nicht an.

Ebensowenig wie den Whisky, der auf dem Tisch steht. Cat trinkt Milch. „Das hilft gegen Lampenfieber und Nervosität", meint er. Vor Lampenfieber

brauchte er eigentlich keine Angst zu haben.

Denn jedes seiner Konzerte ist ein Erfolg:

Die Fans in Deutschland haben ihn nicht vergessen, obwohl er im April 1974 zum letzten mal in Deutschland war. Seine Platten tauchen nur selten in Hitparaden auf, trotzdem bekam er kurz vor dieser Tournee eine goldene Schaltplatte. Endlich wird es dunkel in der Olympiahalle. Nur ein weißer Scheinwerfer flammt auf, reißt zwei hellgekleidete Zauberer aus dem Dunkeln. Sie schieben vier farbige Kästen auf die Bühne, stapeln sie aufeinander, öffnen die vorderen Türen und Cat Stevens tritt heraus.

Begeisterter Jubel

empfängt ihn. Moonshadow ist der erste Song, den er bringt. Ohne Pause schließt sich Another Saturday Night an. Da endlich hebt sich während des Orgelvorspiels auch der Vorhang. Strahlend schön

wird das Bühnenbild sichtbar: eine weiße Leinwand, die von farbigen Scheinwerfern angestrahlt wird. Ein risiger Stern aus Glühlampen, in dessen Mitte immer wieder neue Dias und zu den Songs

passende Motive auftauchen.

Cat Stevens will mit diesem Bühnenbild und dem Baldachin darüber das Universum darstellen, unter dem die Menschen in Frieden leben sollen. Das ist seine Botschaft, die er bei seinen Konzerten

weitergeben will.

Bei dem Song Whistling

Star setzt er sich an den schwarzen Flügel. Es ist sein erstes Lied, zu dem er keinen Text singt, sondern nur pfeift. Dabei wird der Trick mit der zersägten Jungfrau gezeigt, den ihr oben im Bild

seht. Für Cat Stevens ist das aber nicht nur Unterhaltung oder Show. Er möchte damit ausdrücken, wie er an Magie oder Zauberei glaubt. Symbolische Bedeutung hat auch seine weiße Jacke, die er

beim Konzert trägt. Für ihn ist sie ein Zeichen der Reinheit und Unschuld.

Cat Stevens hat an diesem Abend bewiesen, daß er immer noch der ganz große Star ist.

[Bravo, 1976]

"Wenn ich Musik hören will,

lege ich keine Schallplatte auf,

sondern setz´ mich ans Klavier

und schreib´ mir welche".

"Meine Einsamkeit war so groß, dass ich kaum noch weiter wusste".

So schildert Cat Stevens die Anfangsphase seiner Karriere. Einer Karriere, die aus einem verträumten siebzehnjährigen über Nacht einen Weltstar machte - und ein nervöses Wrack.

"Ich kippte jeden Tag eine Flasche Schnaps hinunter und war bei jedem Auftritt stoned". Die Maschinerie des Showgeschäftes drohte ihn zu zermalmen, da wurde er mit offener TBC ins Krankenhaus eingeliefert. So bedrückend die zwei Jahre im Sanatorium für Cat Stevens waren, sie hatten auch einen Vorteil: Der stille, romantisch veranlagte Stevens, der immer nur einfache Lieder und keine aufgedonnerten Hits produzieren wollte, konnte sich aus den Fängen seiner ersten Plattenfirma befreien.

"Über mich singe ich in Moll, über andere in Dur"

"Der Bruch war endgültig. Ich atmete auf, als ich nicht mehr von geldgierigen Managern hin- und her geschubst wurde. Ich wollte nichts mehr mit all den cleveren Geschäftsleuten zu tun haben, denen es egal war, ob ich vor die Hunde gehe".

Steve Georgiou, so der richtige Name des Sohnes einer Schwedin und eines Griechen, nahm sich vor, seine zweite Karriere selbst zu lenken. Gelegenheit dazu bekam er sehr schnell. Die junge, progressive englische Schallplattenfirma "Island" garantierte dem scheuen Songwriter Stevens alle Freiheiten. So entstand das erste wirklich typische Cat Stevens-Album: "Mona Bone Jakon". Die Naivität und Schönheit der Stevens-Songs unterstrich der Sänger noch mit einem selbstgemalten LP-Cover.

Das Publikum reagierte enthusiastisch. Da sang einer wunderschöne Lieder, drückte mit einfachsten Mitteln tiefe Empfindungen aus und blieb bei alledem immer er selbst.

"Was es über mich zu sagen gibt, ist in meinen Liedern enthalten", beschied er Reportern, die mehr über ihn und sein Privatleben erfahren wollten. Es gibt kaum einen anderen erfolgreichen Künstler, der sich so konsequent vor der Öffentlichkeit versteckt wie Cat Stevens. Als sei er ununterbrochen auf der Flucht, reist er von London nach New York, von dort zurück nach Griechenland oder in die Schweiz und taucht dann wieder in Brasilien auf. Kein Zweifel: Cat Stevens braucht die Zurückgezogenheit.

"Das Leben erschreckt mich oft, und wenn ich es nicht auch in so vielen Bereichen lieben würde, hätte ich es ziemlich schwer." So ehrlich, wie Cat Stevens in seinen Songs ist, die oft auch, wie etwa "Lady D´Arbanville", von eigenen Erfahrungen und vom Tod handeln, so konsequent ist er im eigenen Tun.

Stevens empfindet seinen Reichtum als peinlich angesichts der Not, die um ihn herum herrscht. Mehrfach flossen aus den Erlösen seiner Schallplatten sechsstellige Summen an Organisationen wie UNICEF: Und vor kurzer Zeit erst gründete Stevens einen eigenen Wohltätigkeitsfond, der notleidenden Kindern zugute kommen wird.

Wenn es um seine Musik geht, ist der 29 jährige ein verbissener Arbeiter.

Als er 1974 auf Welttournee ging, erwarteten seine Freunde, dass ihn die Strapazen in die Knie zwingen würden. Das Gegenteil war der Fall: "Man darf sich ganz einfach nicht zu einer Maschine umfunktionieren lassen, sondern muss sich immer vor Augen halten, dass man Lieder macht und damit sein Publikum erreichen will. Natürlich habe ich am Anfang meiner Karriere davon geträumt, ein Popstar zu sein, aber das ist niemals bis zur Selbstaufgabe gegangen. Ich kann meinem Publikum jedenfalls mit gutem Gewissen gegenübertreten".

Nicht alle seine Langspielplatten waren so erfolgreich wie "Tea for the Tillerman" oder "Catch Bull at Four". Für Cat Stevens ist jedoch der Erfolg der geringste Maßstab. "Foreigner" war vielleicht ein falsches Album. Es hat viele Leute erschreckt. Aber ich wollte zeigen, dass wir irgendwie Fremde sind. Ich jedenfalls habe mich auf der Welt noch nie so richtig zu Hause gefühlt".

Was diesem scheuen Songwriter bleibt, ist der Reiz, musikalisch noch längst nicht alles erprobt zu haben. "Ich habe nur ein Ziel: Mich weiter zu entwickeln und zu verbessern". Wenn man "Izitso", Cat Stevens´ letzte LP, hört, hat man allerdings das Gefühl, dass es nicht mehr allzu viel hinzuzulernen gibt - musikalisch jedenfalls. Und vielleicht wird er sich ja nicht nur vom Leben eines Tages erschrecken lassen, sondern auch damit fertig werden. Irgendwie.

"oh very Young"

mit 17 schrieb Cat Stevens seinen ersten Song

Stevens privat. Er stiftete für Kinderhilfsorganisationen und richtete seinen Eltern ein Restaurant ein.

[Rocky 1977]

A cat who walks on his own

"Being on stage makes me nervous.

I’m scared people expect to much."

Ask Cat Stevens if he is happy and he tells you:

"It's a good time for me - I'm content - I've got most of what I want."

What then is it he wants but doesn't have?

"I want to be happy." says Cat Stevens.

This brief snatch of conversation may give you some indication of the complexities of the Cat, a star for ten years now and still staggering as he comes off the bend on the final lap of a marathon identity crisis.

A teenage success with a bunch of pop singles like "I Love My Dog" and "Matthew and Son." Stevens—he will be 30 next month - caught tuberculosis and was out action for a year.

It was during this period of recover and convalescence that he plunged into the serious self - examination that was radically to change his direction of his life and his work.

"That’s when I grew my beard, which is now my identity," he says, peering from behind dark glasses In his New York hotel room while on a visit from his home in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Paper

"In the hospital I covered all the mirrors with paper for a time because I really was going through this problem of finding my real self.

When I finally took down the paper there was this beard: And it looked so right.

I believe that any trauma can be used positively or negatively.

After my illness, for example, I could say, gone through life worrying about not having enough jumpers on. But instead I said to myself. ‘Wow! I’m happy to be alive, and took a direction I’d missed before."

Physically that direction took him to Rio. Looking for sunshine, he jumped on a plane, having no Idea how far away Rio was, and liked it so much that he decided to stay.

"I arrived the week before Carnival I and all these incredible people were dancing through the streets, I thought the whole place had gone mad. Then I got the bug and now I get a terrific creative charge just from being there."

Son of a Cypriot father - dad still runs a restaurant in the West end of London - and a Swedish mother, Cat is sensitive, perceptive and as the ten original albums he has made prove, vastly talented.

When it comes to interviews, however, he is far from articulate, a fact he recognizes and acknowledges at one point by grinning and saying "Sorry I can’t remember what we were talking about."

We were talking about his shyness.

"I’m basically shy. That’s why started writing songs as a way of expressing myself.

I like being on stage, but that makes me nervous, too. I’m scared that people will expect too much. All I’m realty selling is my own taste, you see, and I want people to share in it, and if they don’t I feel rejected."

Stevens says he has shed most of the feelings of guilt that once inhibited him. One of them was over the amount of money he earned, but now be is involved with a number of charities, a subject he is loath to discuss.

"The funny thing is" he says, "as I live in Rio everybody thinks tax exile, yet the amount I’ve spent on traveling and doing this and that, well, I don’t think that I’m any better off than I would have been had I stayed and paid the tax."

With his latest album, "Izitso," in both the British and the American charts and the single from it, " Remember The Days of the Old Schoolyard" and set for chart entry, professionally standing has never been higher.

Privately, however, he is something of a loner. A single man, he has nobody with whom to share his Success.

"True" he says, "and that does occupy my thoughts. But I believe that God give me that, vhen the time is right.

I believe in Allah, in God and in living by his laws. I’m not afraid of death - if one Is going to be afraid of something, it’s eternity that scares me!"

Having demonstrated that his is an enduring talent, Stevens is wealthy enough not to have to worry where his next guitar string is coming from. What then keeps him working?

"Yes, I could stop today doing what I’ve always thought I was meant to do. But there are so many things left unsaid. There’s always something more to say… It’s when you have nothing left to say that you’d better shut up"

Deal

He does not see a great deal of his family, but Cat - he’s really Stephen Georgiou and they still call hint Steve - maintains a close relationship with them.

"Dad’s restaurant is doing really well because it’s Jubilee year," he says.

"The first question I always ask him when I phone is, ‘How’s business?' And he always says: ‘How’s business with you?’"

He smiles broadly.

Business is obviously cool for Cat.

[Daily Mirror, 25.06.1977]

CaTNiP

CaTNiP